The Thieves Who Steal Sunken Warships, Right Down to the Bolts

How could someone (or many someones) steal a single multi-ton ship—let alone three or four—without leaving a trace?

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Last November, a team of international divers departed the Indonesian island of Java on a mission to survey sunken World War II warships. The Dutch government had tasked them to assess the condition of two particular Dutch vessels, the Hr. Ms. Java and Hr. Ms. De Ruyter, both sunk in 1942 during the Battle of the Java Sea, not far from the remote island of Bawean.

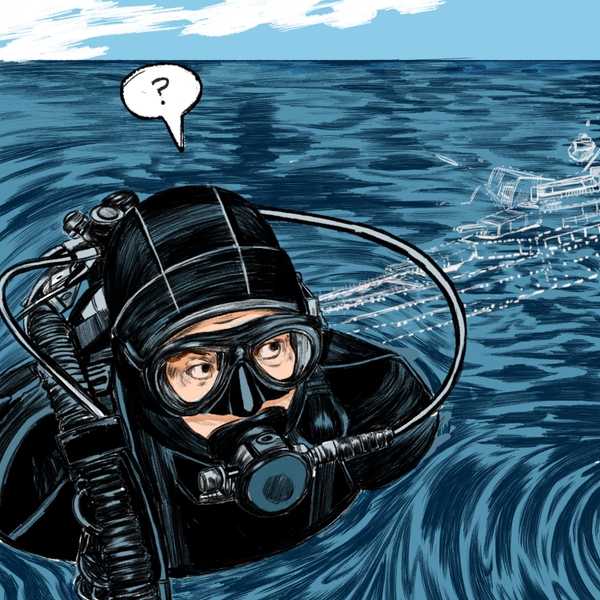

Conditions there are notoriously dangerous: Seemingly endless schools of stinging jellyfish and currents capable of sweeping away even a master diver. Those same currents also kill visibility underwater, limiting it to as little as an arm’s length. Ocean depths in this area can be more than 200 feet, so the dive team knew they’d have to get pretty far down to see any sign of the ships. But as they descended deeper and deeper, the ships remained elusive.

In moments like that, a good diver can’t help but run through a quick mental checklist: Are we using the right coordinates? Did we properly set the anchor? Have we begun to drift?

As the seafloor came into view, answers to a few of those questions became clear. The divers had not drifted. Their anchor had held. And they were in precisely the right place. The ship, on the other hand, was not.

What these divers should have found was a 6,440-ton cruiser, complete with tower, turrets, and catapult—a ship long and large enough to launch a seaplane. Instead, they found only the impression of a hull on an empty seafloor. The vessel that had once lain there had first been discovered in 2001. It was surveyed a year later. Since then, recreational divers had visited. And sure, ocean currents can drag debris from a downed plane or even cause a renaissance galleon to resurface. But this was a massive steel ship. The only way it was going to go anywhere was if someone—or lots of someones—had moved it.

The team’s search for other battle casualties in the area was no less haunting. USS Perch, a 300-foot-long American submarine, was gone. So were two British ships—the 329-foot HMS Encounter and the 574-foot Exeter. Another, the 329-foot HMS Electra, had been gutted. A huge section of the Kortenaer, another 322-foot Dutch warship, was also missing. Seven ships in all—either lost without a trace or grossly scavenged. An eighth, the USS Houston, was mostly intact, but it was clear pirates had begun gutting it as well.

The very nature of these warships is what makes them both so difficult to remove from the ocean floor and so appealing to illegal salvagers ballsy enough to try. Consider this: The Perch, which was as long as a football field and 26 feet wide, displaced nearly 2,000 tons when submerged. The Encounter and Exeter belonged to a robust class of British destroyers that carried torpedoes, anti-aircraft weaponry, and a complement of about 150 sailors each. The De Ruyter was the largest of all, with a length of more than 560 feet. All now gone without a trace.

The divers had not drifted. Their anchor had held. And they were in precisely the right place. The ship, on the other hand, was not.

Whereas modern-day commercial ships are often designed to be as light as possible, warships are built painstakingly heavy: fuel costs aren’t a big issue if your budget is funded by Congress, and the threat of battle makes concerns like hydrodynamics an easy second to the survival of those on board.

Legendary diver John Chatterton has been exploring these types of vessels for decades. He first made a name for himself as part of the team that discovered a German U-boat off the coast of New Jersey in 1991. Since then, Chatterton has dived on dozens of legendary wrecks and starred on the History Channel show Deep Sea Detectives. He says it’s the very construction of these behemoth ships that makes them so appealing to illegal salvagers. “When it comes to scrap, it’s all about the tonnage. If you went out to scrap a modern-day coastal freighter, you’re not going to find much to it. But a World War II riveted hull, you’re talking about lots and lots of structural steel.”

Even in poor condition, gleaned steel fetches about $150 a ton in international markets. A recovered destroyer can easily result in a profit of $100,000—hardly a fortune by many standards, but a lot of money if you’re struggling to get by in a developing nation.

There’s a ton more money to be had if you find ships built before the dawn of nuclear testing. Steel is made by melting iron at super-high temperatures and infusing it with carbon. To make sure those carbon levels don’t get too high, steelmakers blow oxygen into the mix, along with ambient atmospheric particulates. That includes radiation. Natural elements like radon create low-level natural radioactivity. We increased those levels exponentially when countries like the United States and Russia began nuclear testing in the mid-1940s. France, England, and China jumped on the bomb bandwagon a few years later. And with each detonation, radioactivity levels in our atmosphere increased. That meant each time steelmakers were blowing oxygen into new steel, they were also blowing nuclear particulates into it.

That’s not true for the steel used to fabricate pre-1942 vessels, which is virtually radiation-free. And its clean status makes this metal particularly valuable for some technical applications of nuclear medicine and, more commonly, the development of nuclear energy and weapons.

No one knows where—or to whom—the steel from these illegally salvaged ships is being sold. Survivors and descendants of the Houston say they don’t really care. Last month marked the 75th anniversary of the ship’s sinking, and they’d planned to commemorate the event with celebrations and quiet remembrance. Instead, they now find themselves pushing for strict new laws in an effort to save the ship and the remains of those who died aboard—even at the expense of continued dive access. Meanwhile, history buffs and amateur divers alike are blowing up online discussion boards with speculation: how could someone steal a single warship—let alone three or four—without leaving a trace?

In a lot of ways, the Battle of the Java Sea set its own stage for an elaborate heist decades later. The United States, UK, Netherlands, and Australia—countries that previously had been reluctant to get involved in the Pacific war—formed an alliance in early 1942, known as ABDACOM (the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command), to see if they could defend against further Japanese encroachment by waging war against that country’s transport convoys.

“At best, ABDACOM was a scratch team,” says Ron Spector, military historian and George Washington University professor of international affairs. The Allies’ defeat was all but certain, thanks to a lack of tactical planning and coordination. “They didn’t even have a common signal book for communication.”

That would quickly spell disaster for the fleet.

On February 27, 1942, the ABDACOM contingent—14 vessels in all, and hailing from all four of the coalition countries—encountered a transport group of 18 Japanese ships. Intense fighting broke out, and, in less than an hour, the Japanese managed to sink the Kortenaer and disable the Exeter. By midnight, only the Houston and HMAS Perth remained. Two days later, they too were sunk as they retreated through the Sunda Strait. In total, the Allies lost ten ships and an estimated 2,100 sailors over that three-day period.

“By the end of the battle, the score was pretty clear,” says Spector. “It was Japan 100, Allies 0.”

The ten sunken vessels—now a kind of mass burial ground—lay in a few compact groups. Three ships were tightly clustered north-northwest of Bawean, four lay to the island’s southwest, and the Houston and Perth rested just shy of the straits. In time, those ships became habitats for a whole host of organisms ranging from coral, sponges, and anemones to coveted reef fish and whale sharks.

That’s not uncommon. Sunken ships make great artificial reefs; in fact, we’ve long scuttled them for that exact purpose. Fishermen know these artificial reefs make for a consistently great catch, so for a long time, only the local fishing community knew the location of some Java wrecks due to limits in diving technology. That changed dramatically about 20 years ago, when recreational diving began to grow in popularity.

Australian diver Kevin Denlay has been at the center of that community for years. He began diving World War II wrecks in the early 1990s. It was an exciting time for the sport: The so-called technical diving revolution had just begun, and divers were experimenting with combinations of breathable gases like helium that would allow them to go much deeper much longer. That technology opened up previously undived wrecks in places like Guadalcanal, where dozens of WWII ships had sunk. Denlay’s team was on the forefront of surveying several vessels there. After they had explored all of the diveable wrecks—about 20 in total—Denlay set his sights on the Java Sea.

The wrecks there are about 150 to 200 feet down, and Denlay knew they came with the threat of decompression sickness. Currents could easily sweep his team out of view of their support boat. Poor underwater visibility there was the norm.

Despite the challenges, Denlay says their work was mostly marked by tedium—long hours aboard their dive vessel, MV Empress, running transects in search of the sunken warships.

They found the first of the Java Sea wrecks in 2002. It took the group another six years of searching to find the last of the eight unaccounted-for Allied warships. Denlay says the Empress’ captain was the only person who knew the exact GPS coordinates for the vessels, and that he only told the respective navies they belonged to. Still, word somehow got out. As information about the wreck discoveries began to spread throughout the international community, a tiny cottage industry of tourist dives grew. But on account of the conditions there, it never took off to the point that the ships had regular visitors.

Sunken warships remain the property of their country of origin regardless of where they are found. Laws regarding their stewardship vary a little from nation to nation, but in general, the ships—and everything on or in them—belong to that country’s navy. There are even more specific rules, both stated and understood, for vessels containing human remains. It’s a code of conduct among divers: Let deceased sailors rest undisturbed.

Denlay says that, for the most part, initial divers in the early 2000s were respectful. Still, valuable parts of the ships began to disappear over the next 15 years: brass fixtures and portholes, a gun shell, sometimes even a ship’s bell. In 2013, one well-meaning sport diver found a trumpet aboard the USS Houston and brought it to the surface, thinking an organization of survivors and descendants might want it. (They didn’t—and promptly referred the diver to the U.S. Navy.)

But even for all this disturbance, the vessels and the lost souls they carried remained mostly intact. Until they disappeared altogether.

Asian waters have played host to illegal salvage operations for years, particularly in places like the South China Sea, where resources are few and policing the open ocean is difficult. Professional divers like Denlay do what they can to scare them off, but they aren’t at any one site regularly enough to make a difference. And there isn’t much protection for the wrecks otherwise. And there’s plenty of reason for scavengers to risk it: A single brass steering station can go for $5,000 or more on the internet. The thousands of pounds of bronze used to make a warship’s propeller can earn about $500,000 in the scrap market. Factor in the fact that a single ship might have two or more propellers, and you’re talking about a significant amount of cash.

For the most part, this kind of theft tends to be a low-tech job. Salvagers pose as fishermen aboard ramshackle boats anchored at the site, and then dive the wrecks for particular parts. Sometimes, they’re audacious enough to arrive with a barge and crane and bring up heavier pieces. They make off with valuable parts first, like those made of brass and copper. But even as salvagers move on to less valuable things like aluminum shafts, they’ll leave plenty of debris in their wake—fasteners, broken metal plating, and of course, the hulls of the ships themselves.

That’s a huge part of what is so mysterious about these Java sea wrecks: Not a single bolt remains. Highly unusual, even for skilled and ambitious salvagers.

Last month, Malaysian officials revoked salvage rights from a local university, where researchers had contracted with a Chinese company to take samples for a study on toxic seepage. However, when maritime authorities conducted a routine inspection of the Chinese vessel, they also discovered pilfered remains of Japanese warships. Could a similar operation have posed as legit in the Java Sea?

Maybe, agrees Chatterton and Denlay. However, scavengers there would have needed a lot more than just a research vessel to pull off the resulting heist.

Both divers postulate that the thieves would have needed a large barge with a massive crane attached to either an industrial magnet or, more likely, a big claw kind of like the one used to grab stuffed animals in a cheap bowling-alley arcade game. Just how big a magnet or claw? Neither Chatterton or Denlay could guess. But they agree that even the biggest known ones couldn’t come close to pulling up a whole ship. Probably, then, the salvagers would have either placed explosives around the wrecks or used a multiton wrecking ball, just like one you might see tearing down an inner-city building.

Either technique would have taken a lot of time and created a lot of detritus. Denlay says he can’t figure out why no one reported such a massive undertaking. Or why there appears to be nothing left on the ocean floor. “In my experience in Asian waters, that’s very unusual. Usually, at least a skeleton of sorts is left. In this instance, all that appears to be left is a big imprint where a wreck once was. That’s what is so surprising.”

“Usually, at least a skeleton of sorts is left. In this instance, all that appears to be left is a big imprint where a wreck once was. That’s what is so surprising.”

It’s not clear who is buying all this scrap or even whether the buyers know the metal has been illegally gleaned. Chatterton doubts that matters in regional markets. “Nobody’s going to give a shit,” he says. “They’re going to take it and melt it down, and no one’s going to be wiser. Steel is steel.”

The sheer totality of these thefts has had real ripple effects in Indonesian communities. In taking away the wrecks, the illegal salvagers have also taken away the fisheries of the area. They’ve also put a big dent in the region’s underwater tourism industry. “It has basically put an end to historical wreck diving in the Java Sea, as the warship wrecks that have been salvaged were the main attraction there,” says Denlay. He hopes news of these thefts will result in much tighter controls both on preserving remaining wrecks and the sale of salvaged scrap metal globally.

“But it’s too late for that now in the Java Sea, at least,” says Denlay. “That bird has well and truly flown.”

Not everyone agrees.

For years now, John Schwarz has been an advocate for the sailors who served aboard the USS Houston. It staffed a crew of 1,008 the night it went down. Schwarz’s father, Otto, was one of only about 300 who survived the sinking. He and others were held captive in a series of Japanese prison and work camps before eventually being liberated in Saigon. Years later, Otto founded the USS Houston Survivors Association, for which John now serves as executive director. These days, the younger Schwarz spends at least as much time worrying about the sunken vessel as he does the handful of remaining sailors.

As early as 2014, naval surveys revealed “unauthorized and systematic disturbance,” including the theft of metal plating and rivets, along with “associated artifacts” on the Houston. Last month, the U.S. Navy’s History and Heritage Command finished reviewing a more recent survey of the vessel conducted by the Australian government. In general, it concluded, the rest of the hull remains intact. But everyone agrees it’s likely the next target for steel pirates. The question now is whether anything can be done to save it.

A spokesperson for the U.S. embassy in Indonesia told me that they have been working in partnership with the Indonesian government “for several years” to protect and preserve what remains of the Houston. When pressed, he said he could not elaborate on the nature of that work. Meanwhile, the head of Indonesia’s National Archeological Center told the Guardian that his country can’t be held responsible for the safekeeping of remaining warships. Indonesia’s navy spokesperson took that stance one step further and told a French news agency that the countries involved need to guard their own wrecks. The Indonesian navy is one of the largest in the South Pacific, but with just 150 vessels, it’s spread pretty thin over the country’s 54,716 miles of coastline, which is second only to Canada in terms of total length.

John Schwarz wants a better answer than that. He worries that the salvage lobby has stymied any U.S. efforts to protect the vessel and that diplomatic ties are further complicating matters. He says he’d love to see regular patrols of the vessels by an international coalition. In the meantime, he believes the only way to save the USS Houston is to prevent any access to it whatsoever—including recreational dives.

There are some precedents for such measures. The iconic USS Arizona, sunk during the attack on Pearl Harbor, is not open to the diving public. Neither is the Edmund Fitzgerald, which the Canadian government closed to all divers in 2006, after a coffee-table book of the wreck purportedly included an image of human remains.

A few years ago, Chatterton and his team planned to dive USS-09, a WWI-era sub that sank mysteriously in 1941, killing all 33 crewmen. They canceled their plans when the captain’s surviving daughter got word. “She didn’t want anyone diving the wreck,” says Chatterton. “It’s not illegal, but do you want to do something expressly against the wishes of family members?” For him, the answer is almost always no. But he knows not every diver is going to answer the same way. “The ethics of it all is really gray,” he says. “You can abide by the laws and still end up hurting someone’s feelings.”

Officially, the U.S. Navy’s position on wreck diving is defined by the Sunken Military Craft Act of 2004. It prohibits unauthorized actions that disturb, injure, or remove sunken military craft. What constitutes a disturbance is another gray area.

Paul Taylor of the Navy’s History and Heritage Command says that, in general, the Navy embraces the kind of diving expeditions undertaken by both recreational and professional divers, including folks like Denlay and Chatterton. He calls them “stewards and effective ambassadors for the protection and preservation of underwater resources.”

They and other teams have certainly located and identified wrecks that the Navy lacks resources to find on its own, often conducting risky dives and painstaking archival research at their own expense. And both men push hard against any prohibition on diving. If anything, they say, their presence deters illegal salvagers who need the cloak of secrecy and anonymity to pull off their heists.

They also argue say that descendants of sailors, the USS Houston notwithstanding, have been largely appreciative of their work identifying last resting places. “We’re diving those wrecks so that we can put names on tombstones,” says Chatterton. He thinks disturbing the wreck can sometimes be worth that. If bringing up artifacts from a ship are going to allow for that kind of closure, it seems a fair investment in closure.

Denlay says he’s willing to take it further than that—maybe it’s time to for systematic disturbance of remaining vessels.

“This wholesale salvage in the Java Sea has proven once and for all that bringing up selected items for museums would have been a whole lot better than having these historical sites comprehensively salvaged and their remains simply sold for scrap to be melted down and lost forever.”