“You will have read about the plot to blow up HQ the Hotel Grande Bretagne. I do not think it was for my benefit. Still, a ton of dynamite was put in sewers by extremely skilled hands.” Thus wrote Winston Churchill in a telegram to his wife of his close brush with death in Athens on Christmas Day 1944.

The “skilled hands” belonged to Manolis Glezos, the Greek resistance hero who, 70 years after laying the explosives, has revealed to the Observer how Britain’s wartime leader came within inches of being killed by communist guerrillas towards the end of the second world war.

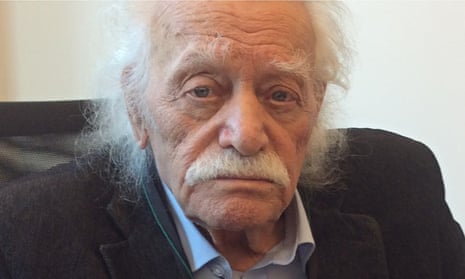

“I will tell you something I have never told anyone,” the 92-year-old said in Brussels, where he is the European parliament’s oldest MEP. “I carried the fuse wire myself, wire wound all around me, and I had to unravel it,” he said, explaining how he spent hours crawling through the sewerage system to plant the dynamite in the dead of night. “There were about 30 of us involved. We worked through the tunnels … we had people cover the grid lines, so scared we were of being heard. We crawled through all the shit and water and laid the dynamite right under the hotel.”

By the time the insurgents emerged, sodden and covered in excrement, there was enough explosive under the building “to blow it sky high”.

“It took me at least two hours laying the explosive material and two hours coming back, and when we came out it was a matter of seconds, it was ready to go.”

But in a twist of fate the attack was abandoned when members of the communist-led resistance movement, EAM, learned that Churchill had flown into Greece and, unexpectedly, was visiting the British command.

“I remember the boys washing us down,” Glezos recalled, his eyes twinkling at the recollection of what would be his most daring escapade during a war filled with heroic feats. “I went over to the boy with the detonator and we waited, waited for the signal, but it never came. Nothing. There was no explosion. Then I found out: at the last minute EAM found out that Churchill was in the building and put out an order to call off the attack.”

The wartime leader, who remained famously unperturbed by his near brush with death having survived at least 10 Nazi assassination attempts, including one reputedly involving an explosive chocolate bar, would escape unscathed.

But the Athens bomb plot was in a league of its own. The would-be attack, barely two months after the Germans had retreated from Greece, came as the country was hurtling headlong into civil war. Athens had been racked by violence after the British army alongside Nazi collaborators – in one of the most controversial episodes of the second world war – opened fire on a crowd of unarmed civilians demonstrating in support of the partisans in Syntagma Square.

The 3 December killings, which kicked off a wave of violence that is known in Greece as the Dekemvriana, are regarded as the opening shots in the cold war. Back in Britain, public opinion was outraged.

With his government also unsettled by the news that the army had turned against the very men and women who for years had been allies in the fight against Hitler’s Third Reich, Churchill made the goodwill gesture of flying out to Greece in an attempt to broker peace. Glezos and his comrades participated in the operation amid heightened fears on the left that the British were bent on restoring the despised Greek monarch, King George II, to power.

After the bloodletting in Syntagma, Churchill had ordered that British troops should seize the city “as if under occupation”, with RAF aircraft strafing working-class neighbourhoods beneath the Acropolis that were known to be leftwing strongholds.

Until now it had been thought that the bomb plot was scuppered only when the dynamite was discovered in the sewers beneath the hotel on Boxing Day. However, Glezos, speaking for the first time in depth about the episode, rebuts that version of events.

“They [EAM] wanted to blow up the British command,” he insisted. “But we didn’t want to be responsible for assassinating one of the Big Three. We wanted to blow up the Grande Bretagne because it was the headquarters of [Lt Gen Ronald] Scobie,” he said, of the man brought in by Churchill to prevent a communist takeover after the Wehrmacht’s withdrawal.

“It was from there that he was directing the battle, that’s why we wanted [to blow it up].”

At the end of the 33-day Dekemvriana, 12,000 EAM fighters and other leftists had been rounded up and sent to camps in the Middle East. Thousands more ended up in hard-labour camps set up with the help of the British on isolated Aegean islands.

Churchill’s obsession with stopping Greece from “going red” was fuelled by his preoccupation with stopping the Russians from reaching the Mediterranean – which was seen as vital in securing routes to India.

Long before the end of the war, the prime minister had fretted about a Russian takeover in Europe, telling his personal physician, Lord Moran: “Good God, can’t you see that the Russians are spreading across Europe like a tide? They invaded Poland, and there is nothing to prevent them from marching into Turkey and Greece.”

That the British army would secure the help of collaborators – members of the infamous Security Battalions which had served under German command during Hitler’s brutal occupation of Greece – in successfully keeping communism at bay is a little-known story.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion