‘You have to address it.’ How San Diego educators are teaching about the Capitol mob

Teachers say they are encouraging students to ask questions, verify facts

Taunya Robinson, an AP US History, government and economics teacher at Patrick Henry High School, was teaching on Zoom about the Cold War when she started getting notifications on her phone about Wednesday’s attack on the Capitol.

“I immediately stopped (the lesson) and said, actually, this is history in the making, so we’re going to stop,” she said.

Robinson told her students to start crowdsourcing social media posts and news articles about the events in D.C. as they unfolded, so they could compare what they found.

“I feel a responsibility to be there for them and to provide them not necessarily with answers, because I don’t want them to feel my views … are the only answers, but to provide them an outlet to ask questions,” Robinson said.

Teachers across San Diego said they felt it was their duty to immediately pivot class discussions to the monumental events of Jan. 6, the day a mob loyal to President Donald Trump stormed the U.S. Capitol building after Trump encouraged them, based on his false claims that the recent presidential election was fraudulent.

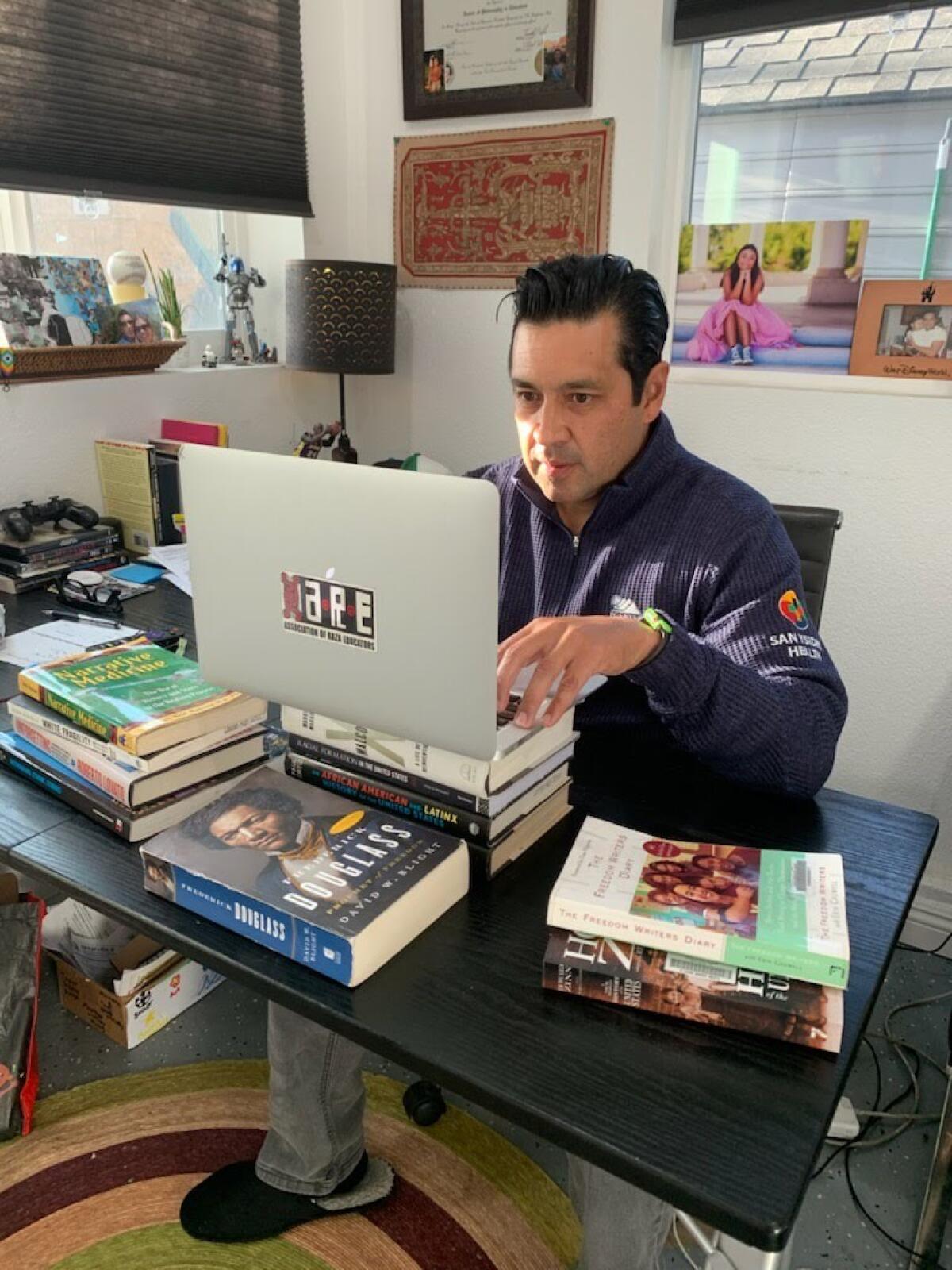

Guillermo Gomez, an ethnic studies teacher at Lincoln High School, said he felt a responsibility to talk about the insurrection with his students.

“You have to address it. It would be a disservice not to address it,” he said.

Some San Diego teachers said students were shocked and anxious about Wednesday’s events. Others said it was surprising how much their students were not surprised.

John Keast, an English, government and economics teacher at Mission Bay High School, said the adults he knows were sending him messages of dismay and shock, while his students were not surprised and seemed to think that Wednesday’s events were “semi-normal.”

Keast said that’s partly because his students have already been discussing current events and the growing polarization of the country during his classes. This generation of young people has been growing up with this new normal that adults are still struggling to accept, he said.

“There is a bit of cynicism that’s being baked into the current generation, and a desensitization, because their exposure on the internet is total,” Keast said. “Their exposure to this stuff has been really traumatic in some ways.”

Many teachers said their students quickly brought up disparities they saw in how Wednesday’s predominantly White Capitol rioters were treated by police and how Black Lives Matter protesters were treated this summer. Students questioned how rioters could break into and loot the Capitol building and not be arrested, while Black Lives Matter protesters have been corralled, shoved, arrested, teargassed and shot by law enforcement while marching on the street.

“They’re noticing the contradictions. They notice that it is a race issue,” Gomez said.

Many teachers said they are being careful to avoid pressing their own beliefs and opinions onto students. Instead they have been encouraging students to ask questions, verify the facts and then come to their own conclusions.

“We want to teach our students not to love or hate our country, but ... to be able to live with it,” Gomez said.

In Robinson’s classes, students discussed topics like the 25th Amendment, the role of police and who was and was not wearing masks at the Capitol, she said. The news about Twitter and Facebook blocking Trump led to discussions about limits to freedom of speech and what private companies can and cannot do in monitoring posts, Robinson said.

Robinson showed them the front page of The San Diego Union-Tribune and asked students to analyze the language that various media outlets used to describe Wednesday’s events, such as whether the people who stormed the Capitol were described as “rioters,” “protesters” or “Trump supporters.”

Her students asked questions such as, why was it taking the National Guard so long to respond, why was this riot not considered an act of terrorism, and was Trump’s inciting of the riot an impeachable offense?

Francia Pinillos, who teaches young adults with moderate to severe disabilities for San Diego Unified’s TRACE school, shared a news article with her students and led a discussion with questions such as: What does it mean to be violent? What is a break-in?

She asked them, how would they would feel if they were working and someone was trying to break into their workplace?

“It’s tricky to modify something so heavy, but we have to be real,” Pinillos said.

Wednesday’s insurrection has added to an extraordinarily high degree of trauma that the country hasn’t experienced since World War II, said Fabiola Bagula, senior director of equity for the San Diego County Office of Education. Wednesday’s chaos is adding to the anxiety students already have been shouldering for months due to COVID-19.

“We’re already in a space where we need to take care of each other,” Bagula said. “It’s our responsibility to hold a healing dialogue space for students and, quite frankly, for our educators as well.”

Bagula said she knows many people may be afraid to talk about events like this, because they don’t want to come off as advocating a certain point of view or they’re afraid student discussions will get heated. But she still encourages educators to not ignore what’s happening.

“It will ultimately impact students’ achievement levels and student health,” she said.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.