No Republican has ever won the White House without winning Ohio. Its enduring title as a battleground state, largely due to the rural-urban divide, is a testament to the range of cultures, values, morals, and opinions it encompasses. While Ohioans might not be able to agree on politics, ask any of them to name an Ohio brewery, and the overwhelming majority will say Great Lakes Brewing Company. As they should. Launched in 1988, Great Lakes is the largest craft producer in the state — 20th nationally, distributing over 140,000 barrels to 13 states — and one of the most revered institutions in Cleveland, by consumers and brewers alike. But over the last few years, a new wave of breweries has been reshaping the craft beer landscape along the shores of Lake Erie. It's not the most mature market in the country; it's not even the most mature market in the region. But Cleveland, with its fleet of fledgling and developing breweries, is becoming a bellwether for national trends and craft beer's narrative arc across the country.

Just down the street from the Great Lakes production facility and brew pub, in the SoLo (South Lorain) District, Paul Benner, Shaun Yasaki, and Justin Carson are about to launch one of the most inventive brewery concepts to-date. Platform Beer Company, conceived as a brewery incubator, will be devoted to outreach and education for aspiring professional brewers. "What we're doing," explains Benner, "is allowing people who are advanced home brewers, maybe somebody who's in the industry, a chance to come in here, brew on our system, have their beer sold on tap, have people be able to enjoy and give feedback, and start creating a brand. We can also help them with business planning, regulations, architecture, design, state and federal mandates."

As the owner of the local home brew store, Cleveland Brew Shop, Benner says, "People come in every day and say, 'Oh man, I'm so obsessed with this, I could see one day making this a living.' It's like a dream, right? But there are no platforms for them to ever launch into their own deal unless they just go it alone or partner with some investor. We want to be that middle ground, where we can help give them all the tools they'll need." To that end, every 12 weeks a new guest brewer will start their course, develop a recipe, brew a beer, and learn about the industry from people who live it day-in and day-out. When their time is up, Benner and his team will throw them a graduation party of sorts and tap their beer for the public to consume. The kicker? Platform is going to offer all this for free.

The brewing side of the model is a 10-barrel production system to complement the 3-barrel guest system. Housed in a 1910s building that originally served as a Czech social hall, the brew houses will be rounded out by four 10-barrel fermenters (with space for ten) and ten 10-barrel serving tanks, all in addition to the two 3-barrel fermentors and the 3-barrel bright tank for guest brewers. All the beer produced in house, and those from a few fellow Ohioans, will be served from 24 standalone taps on a state-of-the-art draft system — one of the perks of having co-owner Carson around, Who also owns the JC BeerTech business, a beer line installation, cleaning, and servicing company.

As for the beer flowing through the lines, Brewmaster Shaun will be leading with yeast-driven styles, including a saison, a Tripel, as well as a tart Berliner Weisse — all styles that are in short supply around the city. "I'm really interested in sour mashing right now, and brewing well-attenuated, dry, drinkable beers," he says. "And nothing will necessarily be year-round. We don't want people to come into the brewery with expectations of what will be on tap. Of course, if something is popular, it will show up again. But everything will be seasonal." When pressed about more accessible styles, Yasaki explains, "We're not going to ignore hoppy beers, but I've got some unique ideas on how to achieve the IPA flavor I like. I'm more into hop flavor and aroma than intense bitterness. We'll have to wait and see how well those ideas work out."

If that ever-changing lineup of hard-to-brew styles and a small barrel-aging program aren't enough, Yasaki and Benner are excited to experiment on a smaller scale when guest brewers aren't around, saying, "That 3-barrel system is going to allow us to do some pretty crazy stuff and not worry about dumping 10 barrels if it doesn't work out." Soon enough, they'll be able to do all the wild stuff they want. Portland Kettle Works delivered the 3-barrel brew house and initial batch of fermentation equipment on April 25, just days after the coating on the concrete pad dried. And with the bar completed and tap lines installed, Platform is on track for a soft launch with its first five beers in June, just before their 10-barrel system arrives. Once that's fired up, it's aiming for a full launch in late July.

But even before the equipment is assembled, Platform has already chosen its first incubator participant: a highly competent, local home brewer with tons of awards to his name. Even as a seemingly ideal candidate, he had to go through a couple rounds of interviews — both for technical knowledge and personality — as well as a thorough vetting of his lineup of beers. Benner explains the rigor by saying, "It's an investment on our part because it's a free program. Once someone goes through it, our intention is for them to go launch a business. That shows that our program is credible, that we've got some proven success." Even more than their track record, the investment can pay off when graduates become advocates and brand ambassadors, helping to spread the word and build a loyal customer base. In the end, Platform is all about people helping people and providing chances for growth and development. Benner puts it best: "If anybody ever started their own business, they're full of shit if they say they never got help from someone. Everybody needs an opportunity."

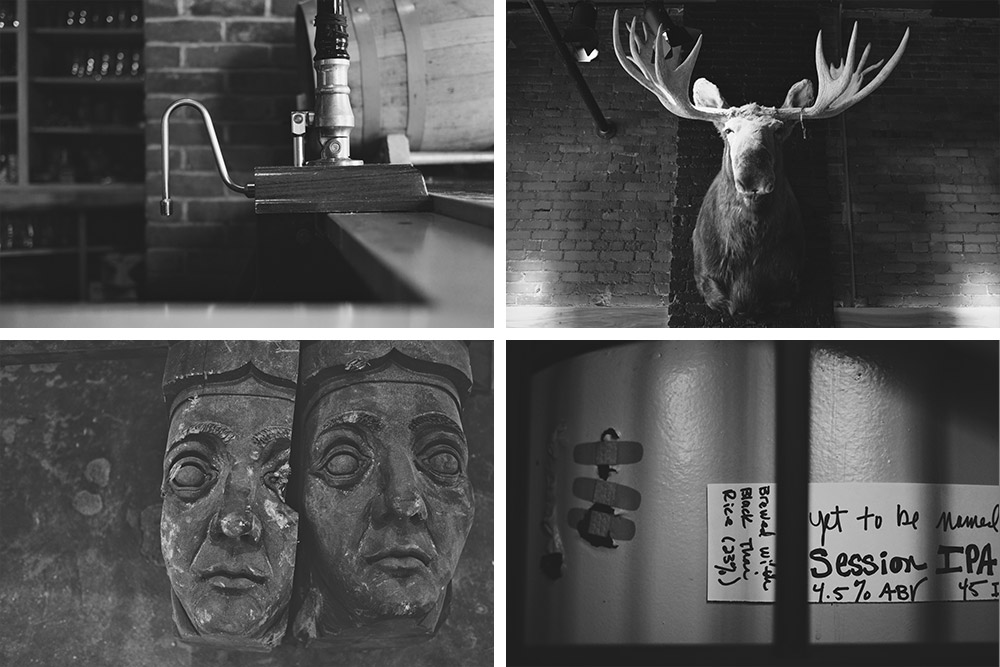

One of those someones that has helped Benner and Platform along the way is Andy Tveekrem. Like so many brewers throughout Ohio, Tveekrem got his start at Great Lakes in the early '90s. After nine years there, he left his post as brewmaster and moved to Maryland, where he eventually became the brewmaster at Dogfish Head. Tveekrem returned to Cleveland in 2010 and partnered with a local entrepreneur. Sam McNulty, to launch Market Garden Brewery, a venture that kick-started the transformation and revitalization of West 25th Street and the entire Ohio City neighborhood. "When we opened, there was about 75% vacancy on West 25th between these three blocks," Tveekrem says. "Now it's zero." At least part of the reason for the limited vacancy is that McNulty and Tveekrem have taken more of it for themselves. In 2012, after Market Garden got off the ground, the two started Nano Brew Cleveland just down the block. In essence, Nano Brew is a fully realized, monetized, and marketable pilot system for Tveekrem and his staff. Not only that, it's arguably the best beer bar in Cuyahoga County. Last year, it was named one of America's Top 100 Beer Bars by Draft Magazine, owing to its lively outdoor Beer Garden Bar and immaculately curated list of 20-plus guest taps. After all, its 1-barrel system can only supply a handful of draft lines.

The 3-vessel brewery, caged off in the back corner of the bar, is humble — the pinnacle of what a home brew setup could be. Once a week, a brewer from Market Garden walks over to fire up the system and create a beer they isn't made down the block, like a rye saison brewed with pippali peppers, or a honey wheat ale infused with green tea. These experiments not only test new ingredients and techniques, but also serve to gauge the beer's marketability. Those that are well-received, like the wonderfully tropical and juicy Citramax IPA, can find a permanent home at Market Garden on their 10-barrel system. "A lot of times, we'll take beer from Market, add something to it, and take it down to Nano," Tveekrem explains, "It's low-risk experimentation. What was middle-of-the-road stuff here will turn into something off-road down there. Then if it works, maybe we'll bring it back." But even though both breweries share beer — and ingredients and ownership and a parking lot — they don't share a lot of the same customers. "Nano has kind of a funky atmosphere. It's got a limited menu, it's smaller, with more of a neighborhood bar feel. We're not going to get the traditional dinner crowd like we do at Market. And the beers reflect that." The two establishments are perfect complements to one another, pushing innovation and consistency at both ends. That will prove invaluable as Market Garden undertakes a massive expansion over the next year, scaling up to a 35-barrel brew house that will crank out over 60,000 barrels per year.

The new brewery, currently being built by Esau & Hueber in Germany, is set to be delivered this October. When it arrives, it will be housed across the street from Market and Nano in the 35,000-square-foot "Fermentation Palace" that's currently being converted from an abandoned warehouse. Once open, the new space will feature a tasting room on two levels, overlooking the iconic and historic West Side Market. "We'll also have a big focus on retail, and we're going to make it very tour-friendly. There'll be catwalks upstairs so people can see above the tank level," Tveekrem says. "We bought a bottling line from a friend of mine out in Kansas, but we'll start out self-distributing, just draft, for the first six months or so. Then we'll get the bottling line going." As far as a distribution lineup, they're going to stick with the big sellers at the brew pub: Pearl Street Wheat, Citramax IPA, some version of their session pale, and Wallace Tavern Scotch Ale. "That one might be a bit of a push," Tveekrem notes, "because it's dark and it's malty. But oddly enough, it has an incredibly passionate following. Not everybody is a hop-head these days."

It's passionate followings like this that Tveekrem hopes can ensure that the expansion is a success. But scaling up isn't without its challenges. "Flavor matching is a big concern for breweries that are expanding," he added. "We won't be doing any single-batches over there; everything will be blending double- or quad-batches to help with consistency." He also mentioned that lab work and quality assurance will be of the utmost importance as the new brewery gets off the ground: "Quality control is what's going to end up hurting the craft community. A rising tide lifts all ships, but that works in reverse, too. Bad beer is bad for everyone, especially locally. We need a lot of these smaller, hyper-local, corner-of-the-neighborhood breweries, but that's where the quality aspect is going to come into play." And that's as true in Cleveland as it is across the rest of the country.

Another Cleveland brewer with quality control on his mind is Matt Cole from Fat Head's Brewery. "We just hired a lab technician, who we're actually sending to school right for a couple weeks in Montreal," mentions Cole. "We're going to start doing more QA. It's important." Like Tveekrem, Cole is in the middle of a pretty major expansion. That the two think alike makes sense; Cole is one of many successful brewers who worked with Tveekrem at Great Lakes in the 90s. Great Lakes truly is the base of the family tree of brewers around Ohio. Further proof of how tight-knit the community is in Northeast Ohio: Shaun Yasaki's job before Platform was with Cole at Fat Head's.

As part of the expansion, Fat Head's has just poured a huge concrete slab at its production facility in suburban Middleburg Heights, about 20 minutes southwest of downtown. The new pad is in anticipation of eight new 170-barrel fermentors that will soon be arriving. "We're at about 12,000 barrels now. Once we get the new tanks in, it'll push us to about 20,000," Cole notes. Casually, he continued, "And then we have room to move back in this direction, and eventually, we'd like to take the building next door. That should be able to put us at about 35,000 barrels. And that'll all happen within four years." The ease with which he talks about tripling capacity was astounding, but it seems like he's found some sort of peace with the thought of constantly expanding. "We just keep growing and growing and growing. I just kind of steer the growth."

It's worth mentioning that Fat Head's just celebrated its fifth anniversary this spring, and only moved into this current production facility two years ago. The space it originally designated for storage is quickly being overtaken by new stainless. "We make beer and ship it out almost immediately," Cole laughs. "It doesn't sit around for very long." Helping to keep things moving is the five-vessel, 25-barrel BrauKon brew house Cole purchased from friends at Tröegs. "I was sitting with them at the bar one day and they say, 'Oh yeah, we're building a new brewhouse in Hershey,' and I'm like, 'What are you doing with that old brewery?' We basically struck the deal over a pint." And a deal it was. Fat Head's purchased the system for a fraction of what it would have cost new. "One guy can have three fucking things going on. It's designed to not stop," Cole explains. "Once you get to a point in your runoff, you can start mashing the next batch. All computerized." The system allows Cole and his team total control over the process, brewing three, sometimes four, batches a day, and usually around 15 per week.

Even with that schedule, they're having trouble keeping up with demand, especially for the beer that put them on the map. "Head Hunter won the West Coast IPA award about four months after we opened," Cole says, "and that led to Draft Magazine's Top 25 Beers in the World, GABF, World Beer Cup, and, gosh, we've won silver back-to-back in the last two World Beer Cups. I did the math, I think it had to go against 400 beers. Statistically, that's fucking amazing." When asked about what kind of impact those accolades have had on the brewery, he replies, "It helps. What it brings is consumer confidence. But that still means you've got to deliver the goods after you blow your horn. 'Cause then you're under a microscope, 'Is it as good as they say it is?' That's where we have to constantly keep reinventing ourselves. Everybody is getting better at this game, and it's harder to stand out in a crowd."

This year, Fat Head's is going to try standing out in arguably the most mature, competitive, and sophisticated market in the country: Portland, Oregon. The West Coast expansion will be the first for any Ohio brewery, and a huge opportunity for the state — and the region — to make an impression in an advanced market. The brew pub will be located in the Pearl District alongside the likes of Deschutes, Bridgeport, 10 Barrel, and Rogue. Cole explains, "Portland is kind of uncharted territory for us. But it's a great beer scene. I'm really excited for that whole thing." He adds, "We're hoping we can capitalize on the fact that we'll be a neighborhood pub. It's a smaller brewery — only a 10-barrel — but we're just littering it with tanks. I think there's like 13 fermentors and 12 brights. Lots of flexibility to a do a lot of different styles. We'll use a lot of indigenous ingredients — hazelnuts, peppercorns — whatever's popular in the market. We're not just going to brew the same stuff we make here and just take it out there. They're going to experience completely different stuff."

Back in his home market, Cole hopes that both the West Coast and Ohio expansions can help increase Fat Head's presence on store shelves. "When it comes to putting your beer in a bottle, it's a dog-eat-dog world. It's a tough, tough market. And there's a lot of mediocre beer. You start charging $9.99 for a four-pack, you better have goddamn good beer, man. That's hard-earned money. That's where this whole quality control thing comes in." In addition to all of the testing equipment, the expansion includes hop-dosing tanks to pneumatically blow flower hops into the fermentors with CO2. Less oxygen exposure will lead to fresher beer coming out of the tanks, which will lead to fresher beer on store shelves. The upgrade for dry-hopping will put them on par with Lagunitas, Southern Tier, and Russian River as far as equipment is concerned — stellar company for a native Ohioan.

With established breweries growing and new breweries popping up every few months, Clevelanders can't seem to get enough craft. Different styles, different atmospheres, different philosophies — anything and everything is welcomed. And it's clear that Great Lakes paved the way for the current appetite. Having a local brewery that's been making great and varied beers consistently for over 25 years has created an open and educated consumer. it just so happens that a lot of those consumers are looking to broaden their palates just as new breweries are coming online. But more than that, the GLBC history has shaped the very fabric of the local brewing community. Everyone is connected, and all roads lead back to Great Lakes, whose culture and attention to detail has prepared the current generation of brewers to innovate, to adapt, to grow, to anticipate market demands, and most importantly, to ensure quality through it all. As many breweries across the nation near three decades of operation, beer drinkers can only hope they each do as much as Great Lakes to nurture and steward the industry they helped create. If they do, bright days lay ahead in Ohio, as in the rest of the country.

This is the first of a three-part series chronicling the state of craft beer in the Buckeye State, and how it could lend insight into national trends and future growth for the industry.