Editor’s Note: Every week Inside Africa takes its viewers on a journey across Africa, exploring the true diversity and depth of different cultures, countries and regions. Follow presenter Errol Barnett on Twitter: @ErrolCNN and on Facebook: ErrolCNN

Story highlights

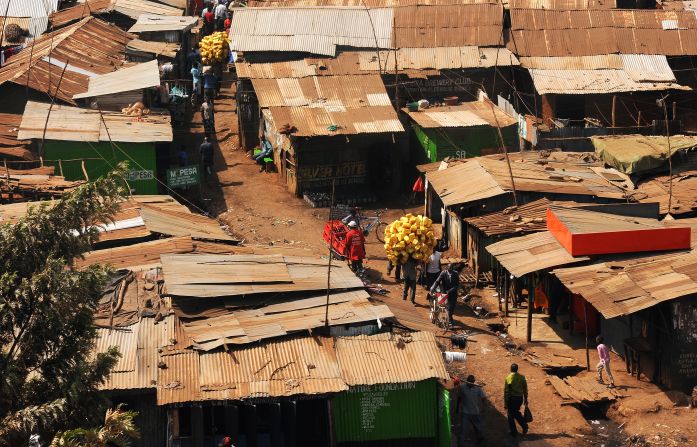

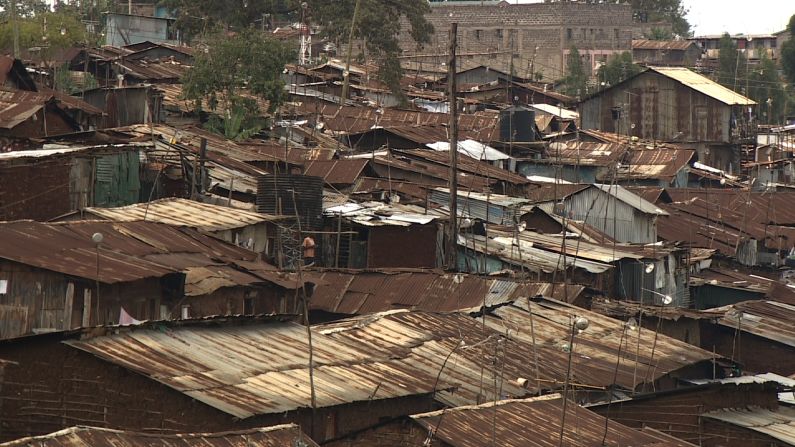

Kibera, in Nairobi, Kenya is one of Africa's biggest urban slums

A million people live there with limited access to water, electricity and other services

But the settlement is also home to a film school, giving locals the chance to express themselves

Many go on to careers in the local film and television industry

Life isn’t easy in Kibera, one of Africa’s largest slums. About one million people live in this sprawling settlement in Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, with limited access to electricity, running water and other basic infrastructure services.

Getting by here demands a rugged resilience from Kibera’s inhabitants – a willingness to help their neighbors, and group together in times of need. But the everyday challenges of life here haven’t been a barrier to local people expressing themselves. The slum is also home to the Kibera Film School, which gives local creative talent the opportunity to tell stories about their world to a broader audience.

To understand their stories, you first have to understand the conditions they live in. Ronald Omondi, a Kibera resident and film-maker who captures the street life of these poor neighborhoods in his movies, has offered me a tour of the settlement to give an insight into some of the challenges faced here.

Kibera began more than a century ago as an informal settlement in the forests outside Nairobi, where the British colonial authorities gave allocations of land to Sudanese Nubian soldiers returning from service with the King’s African Rifles. From these small, forested plots, a vast settlement has sprung in an haphazard, unplanned way, leaving residents without access to fresh running water in their homes.

“The pipes that supply clean water to the slums are broken,” says Omondi. Instead, the locals have rigged pipes to the city water supply. They collect water rations in containers wherever they can find it: From overflowing dams during the rainy season, as well as burst pipes.

“When pipes burst like this, some get (it) free and some are paying for it,” says Omondi.

Read also: Urban rebirth: Johannesburg shakes off crime-ridden past

A similar approach is taken to bring electricity into homes, with residents rigging up their own unofficial connections to city power lines to power their homes.

Because the inhabitants of Kibera are among Nairobi’s poorest, the goods in its markets are sold at very low price points. Cigarettes are sold singly, and most of the clothes for sale are second-hand: A pair of used jeans can be bought for about $2.

Homes are built of a mixture of concrete, mud and wood, often by the labor of locals pitching in to help each other. There are no toilets inside.

“People come together because they like helping each other,” says Omondi. “Some decide to build a house because (there’s) no employment around.”

Some of those underemployed residents are finding an outlet through the Kibera Film School. The school was founded by American film-maker Nathan Collett, who came to Nairobi in 2006 to research African storytelling. In collaboration with locals, he made a short film, “Kibera Kid,” which went on to win a number of international awards.

He subsequently launched a non-profit to start the Kibera Film School in 2009, with the aim of providing local people a chance to tell their stories through film, and gain the skills to work in the local film and television industries.

Read also: Messi leads African literacy bid

Omondi once made a living selling CDs while he studied electrical installation at a local technical institute, before he heard about the opportunity to train at the school.

“I realized I have a lot of talent in camera work and filming, and that’s when I applied,” he said.

Having discovered his passion for film-making, Omondi has made a number of projects – documentaries about schools, commercials, and a feature film on the gangster scene.

And today, he has returned to the school to teach photography. “I feel like I want to use this talent to give back to the community,” he says.

Many other graduates have gone on to successful careers in the industry.

“They found the right way, and the right channel to follow,” he said. “Most of them are working in big companies with(in the) film production industries.”

He said the school was “transforming lives of people living in slums… How they think and want their thoughts to be seen visually.”

As for him? “I think it’s changing my life,” he said. “I see big changes.”