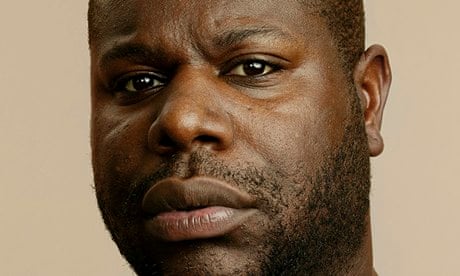

Steve McQueen has known about slavery for as long as he can remember. To the son of West Indian parents, slavery's history is the story of his very existence: "So there is a weight on your chest, on your back, from a very early age." Yet he cannot recall having ever felt angry about it.

"Angry?" He looks puzzled. "No. You feel hurt that someone did such things, but angry? No." To McQueen, the notion sounds as bizarre as finding slavery funny. "Painful, sure. Hurt, absolutely. I don't know if that can be seen as anger. Not to say that I'm not angry with injustice, of course – and slavery is a huge injustice. But thinking about it that way? No." From his baffled expression, you might think him literally unaware that anger is quite a common response.

Like many artists, McQueen experiences the world from a highly singular perspective. As a working-class boy growing up in 1980s suburbia, "there were no examples of artists who were like me. When did you ever see a black man doing what I wanted to do?" His father kept telling him to get a trade; even when his son began to be successful, "he was still taking the piss, saying to my friend, 'Do you understand what Steve does?'" McQueen's first film, Bear, was 10 minutes long, silent, and consisted of two naked men, one of them him, wordlessly circling each other, staring and sparring.

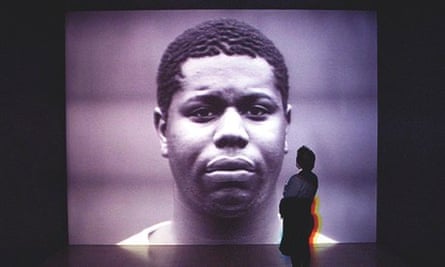

He has never been interested in pleasing mainstream tastes, but no matter how uncompromising his work, it keeps becoming more and more popular. After winning the 1999 Turner prize with a video installation filmed from an old oil drum rolling through Manhattan, he was awarded an OBE, followed in 2011 by a CBE. His first feature film, Hunger, released in 2008, was a remorselessly gruelling portrayal of Bobby Sands starving himself to death in the Maze prison, and not an easy sell, but the critics went wild and McQueen won a Bafta. Shame, his second movie, could not have been a less sexy study of sex addiction, but took more than £10m at the box office. The director shot his latest movie in just 35 days, with one camera and a budget of barely £10m, and wasn't even confident of finding a distributor brave enough to take it. This week 12 Years A Slave opens in Britain, having already earned $40m (£25m) in US ticket sales, multiple Golden Globe nominations and countless predictions of an Academy Award that would make McQueen the first black feature film director to win an Oscar.

We meet for lunch in Amsterdam, where he decided to live 16 years ago, "because it's not London, it's not LA, it's not New York". He lives there with his long-term partner, a Dutch film critic, and their two children, a son and a daughter. McQueen is more elegant than photos tend to suggest, and has the most amazingly fluid face, which looks completely different from one moment to the next. His voice is never static, either, swaying between estuary mumbles and a thespian baritone, so every few minutes it feels a bit like having lunch with someone new. But he is always businesslike and polite, and so engaged that you would never sense that this is probably the umpteenth time he has discussed his new film.

12 Years A Slave is based on a book McQueen's wife came across while he was working on an idea about a free African-American from the north kidnapped into slavery in the deep south. Its author, Solomon Northup, had been exactly that: a prosperous black New York businessman, drugged by traffickers and sold into slavery, who escaped 12 years later and published a memoir detailing the horror of Louisiana plantation life. McQueen couldn't believe his eyes. "It was identical to my idea. But every turn of the page was a revelation, because you think you know what slavery is, and you're opening this book and thinking, my God. Every page was just, wow, really? It was such an eye-opener."

McQueen's film pitilessly documents the beatings, lynchings, rape and brutality of a slave-owning class half-demented by its own moral corruption, and routinely reduces audiences to tears. "I hadn't realised slavery was that bad," is the comment its director keeps hearing.

"There's been a kind of amnesia," he says, "or not wanting to focus on this, because of it being so painful. It's kind of crazy. We can deal with the second world war and the Holocaust and so forth and what not, but this side of history, maybe because it was so hideous, people just do not want to see. People do not want to engage."

Only it turns out that they do. At screenings all over the US, Q&A sessions have become "more like town hall meetings, because people have got so much to say. It's almost like the film has given people a platform. It's been amazing. The film has evoked a conversation about that time in history that I don't think has happened for a long, long time. It's been incredible."

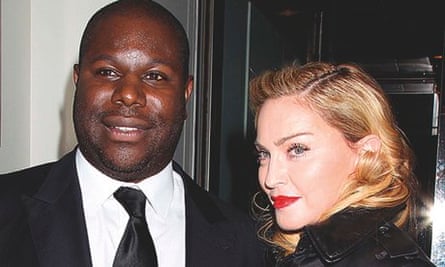

While thrilled by the film's reach, however, McQueen has been thrown by the unintended consequence of success: at 44, he finds himself the new darling of Hollywood. Benedict Cumberbatch co-stars alongside Michael Fassbender and Chiwetel Ejiofor, and Brad Pitt appears, too, having been quick to come on board as a producer. Even Madonna was all over McQueen at the New York premiere – though she spent the entire film texting, which he says made him laugh. Lavished in a froth of celebrity attention he'd neither anticipated nor sought, McQueen smiles wryly, "It's almost like I've seen behind the curtains." Then the smile vanishes. "You know, I'm not so interested in that. I'm only interested in the work. So all this chat, all this, you know, selling your soul, that's of no interest. To me, it's all about the work. It's the only thing one can do."

McQueen is a famously abrasive interviewee: one film critic who caught the sharp edge of his tongue at a recent press conference wrote that he was "a dick" who "acts like he's genuinely baffled as to why anyone is asking him any of these questions at all". Admirers prefer to say he doesn't suffer fools gladly. But what can look deliberately obtuse or contrary is often something else.

For example, critics frequently observe that all his films have dwelt on the body: Bobby Sands' emaciated frame, Shame's sexual compulsions, the livid welts left by a slave owner's whip. McQueen has always claimed to have no idea what they're talking about. "Well, everybody's using their body in a movie," he objects. "I mean, how are they not? I don't understand the point." But the problem turns out to be the phrase "the body". He thinks it sounds pretentious. He was too embarrassed even to call himself an artist until about five years ago, for fear of sounding grand; if anyone asked what he did, he'd say, "I make work. I make stuff." When I suggest "physicality" instead of "the body", he instantly relaxes, and agrees it's a recurring theme. "Yes, the physicality, the body – maybe, like, the art is the body. I suppose that's right."

His work also explores the nature of authority, and the choice between collaboration and resistance. I wonder if this is because he is curious about how he would respond in circumstances such as Northup's or Sands'. "I've had no choice but to resist. For me, it's been all or nothing, that's it." I'm not surprised by his answer, but I am curious to know why. "I don't know, it was all through childhood, I think. Maybe that's the key. It all goes back to childhood." I'm sure he's right. The trouble is, I've seldom met anyone more determined to leave their childhood behind them.

The most obvious theme in all three films is incarceration, physical and psychological, so I ask if he knew anyone in jail while he was growing up. He says not. Does he have any idea where the preoccupation with imprisonment comes from? "I don't know. I mean, you're the journalist, that's your job. I just get on with it." Then he looks a bit put out. "I think sometimes people have pre-ideas about me. I mean, I don't know how people can ask that of anyone: 'Have you ever been to prison?'" But I didn't. "Yes, you did." No, I asked if he'd known anyone in prison in his childhood, because incarceration is such a powerful theme in his work. "I take it back, I apologise. You're absolutely right," he says at once, and thinks for a while.

"Often people think they're powerless in a situation and actually, by making some kind of efforts, you're not. You can actually break free of that. You can actually…" And then he breaks off.

"I don't know, I'm struggling. I'm struggling here. I've never examined myself. This is hard because I'm going back to certain times in my life I haven't really thought about for a long time. And maybe I avoided that because it was always a very difficult time in a way, and a lot of people were damaged on that journey, friends of mine. And it was all because of people not giving a fuck."

McQueen was born in west London to Grenadian parents, grew up in leafy Ealing and went to a very multicultural school where he was one of the cool kids, on account of being big and good at football. "It was fun, we laughed all day, I didn't do any homework ever, we just laughed." When I ask about his relationship with authority as a child, he replies lightly, "Authority was good, that wasn't a problem. I wasn't a troublemaker, I was good." But then I ask when he has felt most powerless in his life, and his expression darkens. "At school. God, that was horrible."

By the age of 13, one class of academically gifted kids had been creamed off for special attention. Then there was 3C1 class: "For, like, OK, normal kids." And then there was 3C2: "For manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." McQueen was put in 3C2. At first, he says mildly, "I don't know why. Maybe I deserved to be," and seems about to drop the subject. Moments later: "That inequality – I fucking loathe it with a passion. It's all bullshit, man. It really upsets me."

When he went back to present some achievement awards 15 years later, the new head admitted to him that the school had been institutionally racist. This did not come as news to McQueen. "It was horrible. It was disgusting, the system, it was absolutely disgusting. It's divisive and it was hurtful. It was awful. School was painful because I just think that loads of people, so many beautiful people, didn't achieve what they could achieve because no one believed in them, or gave them a chance, or invested any time in them. A lot of beautiful boys, talented people, were put by the wayside. School was scary for me because no one cared, and I wasn't good at it because no one cared. At 13 years old, you are marked, you are dead, that's your future."

He doesn't want to think about what his future would have held had he not been able to draw. "Not good. Not good." But his talent for drawing saved him, and when he stayed on to take A-level art, he got to know the kids who had been the school geeks in the higher sets. "And I realised they were just so cool." They would all watch Dennis Potter's The Singing Detective and talk about it, and suddenly McQueen was having conversations he'd never imagined. After a few false starts at local colleges, he applied to Chelsea College of Arts, didn't have the grades, but got in on the strength of his portfolio.

Unsurprisingly, the sociocultural landscape of art school in Chelsea might as well have been another planet to McQueen. But he didn't notice. "No, never. For the first time I was happy. I had an environment I could work in, and so I was happy. I think I'm like Mr Magoo a lot of the time, you know. I just focus – focus on my work. I just wanted to focus on that."

After graduating from Chelsea and then Goldsmiths, at the tail end of the YBA scene, when Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin were busy capturing headlines, he moved to Amsterdam. He says he cried when his daughter started school, because "it was just so beautiful, how the school was. It was so different." Private schools don't exist in Amsterdam, and the city's quiet egalitarianism had been part of its appeal.

But in the past McQueen has said he chose Amsterdam chiefly because "no one comes here, so I'm never bothered." It occurred to him recently that he has "hardly any friends", when he looked at his phonebook and realised almost every number was a work contact. "But that's cool. That's good." I'm getting the impression that beyond work and family, the rest of the world doesn't figure much for McQueen. "It does, it does," he says at once, then stops and asks himself, "How does it, Steve?" Struggling to come up with an answer, he stalls. "Well, in what way, for example?"

Well, most people would be able to name at least one thing outside work and family that means the world to them. It could even just be a football team. "Oh well, I gave up football. It affected my day too much. It's just stupid." He used to be a fanatical Tottenham fan, until he decided not to be, and he now no longer gives the club a thought. Is there anything else important in his life? He thinks hard, and comes up with nothing. "Well, my work just takes up a lot. I mean, I don't 'go to work', I don't have a studio, it's just happening all the time, at the kitchen table, hovering, in bed. I wouldn't call it my work. I'd call it my life."

It's that fusion that makes his life interesting to anyone who follows his work. But McQueen seems uncomfortable with self-examination, so I'm surprised when he calls a few days later to say, "I thought we hadn't really finished the conversation last time. An hour and a half isn't long enough to get there – and I want to get there, wherever it is, I don't know." It's true, he agrees, that he doesn't like talking about his childhood. "I tend to not think too much about that. But I thought the school stuff was interesting. It was a very early stage of my life to see the discrimination against black and working-class people, and I needed more time to think about that. It takes time."

Then his voice becomes slightly strained. "I've never said this before, ever. But I was dyslexic. And I've hidden it, because I was so ashamed. I thought it meant I was stupid." He pauses. "Also, I had a lazy eye. So I had a patch. When you're in front of the chalk board, you still can't fucking see. So it was a terrible start. And people make judgments very quick. So you're put to one side very quickly."

It's the second time McQueen has mentioned shame. The first was when he talked about learning about slavery – "All I remember feeling was a real sense of shame and embarrassment about it" – and that emotion may explain why he had never set foot on a film set before making Hunger, nor watched almost any other film about slavery before making 12 Years A Slave, including an earlier TV adaptation of the book. He can't remember the last time he watched his own films, and when I ask what he's learned from earlier mistakes, says, "Mistakes? I don't really believe in mistakes. I don't really have many mistakes in that way." But what can look like implacable self-belief may be the insecurity of someone who can still hear the memory of his own father's mocking scepticism, and cannot afford to entertain doubt.

His reluctance to revisit past wounds seems to have led to a blanket embargo on curiosity about himself, which I think has leaked into his work because, despite having made three films about human survival in states of extremity, none has even begun to unravel why people behave as they do. His protagonists' pain is always privately contained, never shared with an intimate or explored through dialogue, so we scarcely know them any better by the final scene. Instead, his films just show what people do – in unflinching detail. So we saw exactly what excrement smeared over prison cell walls and crawling with maggots looks like, or a sex addict masturbating in a toilet cubicle, and now we see exactly what a slave looks like hanging from a noose, while other slaves avert their gaze. But we never see inside their minds. For McQueen, the visual artist, showing what they look like is what matters.

When I ask what new ideas or emotions he thinks the film offers, he admits, "I don't know. I was just interested in telling the truth by visualising it. Visualisation of this narrative hasn't been done like this before, and I think that's the thing. I mean, some images have never been seen before. I needed to see them. It's very important. I think that's why cinema's so powerful."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion