It is widely accepted that language evolves, but how does one identify the very important moment in the flux of debate when the meaning is settled? Out with the old word or expression: commit to the new.

Colleagues, as well as readers, are alert to changes in the use of language in the Guardian; complaining on occasion that we are relying on an outdated word or phrase. Many of these concerns are passed straight to David Marsh, who edits the Guardian’s style guide, but issues are often raised in the readers’ editor’s office, too.

A story published on 15 January with the headline “Academy president disappointed with ‘all-white’ Oscar nominees” prompted a worry from a news editor during the editing process.

He emailed me: “I have noticed the creeping use of the term ‘people of colour’ … which I feel a bit uncomfortable about … what do you think? I took it out of a piece on our pages earlier this week…”

I admit I wondered whether I had missed something, for I was reasonably sure that it was an acceptable phrase but had something changed?

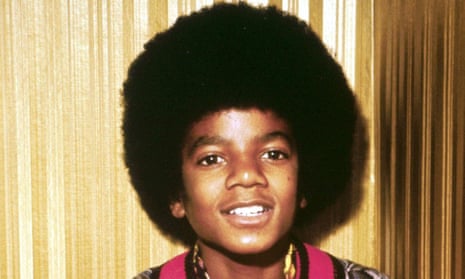

Over time the term “Afro-Caribbean” was deemed outdated because of the word “Afro” being connected to a hairstyle rather than a continent. Rightly – as recognised in the Guardian’s style guide – it was replaced with African-Caribbean.

Although “people of colour” is not in the style guide it is a term that goes back to the 1980s. It is still much more widely used in the US, where some commentators are uncomfortable with its closeness to “colored”. Its unfamiliarity in the UK might have been one reason for my colleague’s concern. But it’s fine, for now.

A few days later a colleague approached with an allied concern about the use of language but with a much bigger canvas – Africa itself. “I am hoping to start a conversation about – and hopefully change – the way we use the word ‘Africa’,” she said.

She pointed to a Guardian sports article with the headline “Two African refugees aim to make history at 2016 Rio Olympics”. It is an upbeat story about two martial arts specialists who hope to be considered for selection in a new category of refugee athletes, who will participate under the banner of the International Olympic Committee.

My colleague said: “The headline simply refers to ‘African refugees’ when in fact both people mentioned are from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. We wouldn’t say Middle Eastern or Asian refugees to mean Syrians, nor would we use Europe to talk about British refugees … Africa is a geographical place, a continent with 54 countries.

“This is not about never using the word ‘African’. I know a headline needs to be succinct and if you have more than one African country it may be appropriate.”

As the use of social media has grown, the voices of Africans are heard more often pinpointing lazy stereotyping and hyperbole. There are websites with a mission to identify such instances. Africa is a country has a strong track record of catching gaffes.

The Daily Maverick, the Guardian’s current partner in South Africa, is a collective of writers from the continent covering everything from breaking news to debates about race.

And contributors to Kenyans on Twitter (#kot) are also formidable in their determination to puncture stereotypical attitudes to their country. When Barack Obama visited Kenya last year they objected to a CNN news report that he was “not just heading to his father’s homeland, but to a region that’s a hotbed of terror”.

As Guardian Africa network’s Maeve Shearlaw wrote: “The hashtag #SomeoneTellCNN began trending on Twitter, as Kenyans fought back against what they called negative, one-dimensional reporting. Many shared images of Kenyan wildlife and holiday idylls to provide a contrast to the ‘hotbed of terror’ label.”

When the Africa network was launched in 2012, David Smith, the paper’s South Africa correspondent, wrote: “…those externally imposed narratives of Africa are shifting. Once they were dominated by conflict, despotism, disease, televised famine and hapless victimhood.

“Now, the talk is of African lions, six of the world’s 10 fastest-growing economies, a booming middle class, a slew of natural resource discoveries, the next frontier for investors – not aid donors.”

I agree, it is a view that deserves journalists’ support.