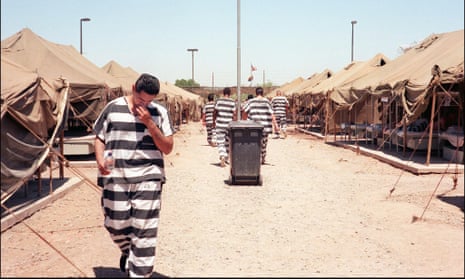

‘Hitler! Hitler!” the prisoners chanted to the TV cameras in protest. It was 4 February 2009. More than 200 Latino men in black-and-white striped uniforms, shackled to each other, were being marched towards an outdoor unit especially for “illegal alien” prisoners in Arizona’s infamous jail, Tent City.

The chants were directed at the Maricopa County sheriff, Joe Arpaio, who a few months before had called this outdoor jail close to downtown Phoenix – his own tough-on-crime creation – a “concentration camp” in a speech to political supporters at his local Italian-American club.

When asked about the comment by the Guardian in July, Arpaio brushed it off as a joke. “But even if it was a concentration camp, what difference does it make? I still survived. I still kept getting re-elected,” he said.

The jail survived too. For more than 20 years, Tent City stood within a larger jail compound in an industrial area 10 minutes south of downtown Phoenix. At its peak in the late 1990s, it comprised 82 Korean war-era military tents and housed 1,700 inmates. After 2009, it could hold up to 200 undocumented immigrants.

Despite multiple lawsuits from mistreated former prisoners, mounting public outrage and intense criticism from groups such as Amnesty International, which derided the facility as inhumane, overcrowded and dangerous, the outdoor prison remained open. Even the justice department accused Arpaio of racially profiling Latinos on his patrols and denying prisoners basic human rights in his jails.

But now, like Arpaio’s own legacy, Tent City’s tenure is about to come to an end, leaving many local city residents, civil rights groups and former inmates asking: how did it survive for so long?

The facility was never meant to be open for two decades. It started as a temporary solution to overcrowding in the other Maricopa County jails in August 1993. Arpaio said it cost just $80,000 to erect, using surplus military tents left over from the Korean war.

For months at a time, inmates sentenced for minor crimes slept under the green cloth tents on bunk beds perched on large cement slabs on gravel. In the summer, temperatures inside could reach up to 54C (130F) in the dry Arizona heat. Though there was an indoor air-conditioned unit where detainees could shower and take sick relief from the heat, they weren’t allowed to sleep there.

Inmates were issued with pink underwear, pink sandals and used pink wet towels around their necks to ease the heat. The sheriff said he chose pink so prisoners wouldn’t try to steal them.

Arpaio had styled himself as “America’s toughest sheriff” since the early 1990s, focusing on the drugs trade and criminal gangs. But in 2007, as the border state of Arizona became the main gateway for more than 50% of undocumented migration and fears grew over terrorism, he switched tack, focusing his ire on illegal immigration. Tent City was a particularly divisive project, inspiring admiration from some in the local community, but drawing intense criticism from those who saw it as a place of humiliation.

Proud of his prison experiment, Arpaio frequently invited the media to witness new cohorts of detainees being sent to Tent City, as he did in 2009. He said this was an inexpensive way to get his anti-immigration message out to the public. Justifying his use of tents and razor wire to the TV cameras and journalists, Arpaio argued that the criminals inside – both Americans and foreigners convicted of minor offences, most often drug use, shoplifting and, in some instances, working with false documents – were “more adept at escape”.

Jaime Valdez, 35, spent four months of 2012 in the separate outdoor unit for around 200 undocumented immigrants. For shock value, Arpaio promoted this wing as a place for “illegal aliens”, but in reality it was for anyone awaiting to be turned over to another law-enforcement agency.

“They mocked us for not speaking the language,” Valdez says of the jail guards. “We would talk to them and they ignored us.” Sent there after a drink-driving conviction, he says the inmates of Tent City “knew we were there because we had made a mistake, but it was denigrating”.

On cold days, temperatures reached as low as 5C (41F). Holes torn in the tents let in the wind and rain, drenching the beds. Valdez and other prisoners made ropes to hold the tent canvases together out of black trash bags they had been given as raincoats.

Inmates were forced to work on chain gangs – which, save for a few exceptions, had been abandoned by the US in 1955. Maricopa County ran the only all-female chain gang in the country. Other detainees had mandatory work inside the jail, and some were part of a furlough programme – still in effect – that allowed them to go outside to work but return to sleep in Tent City. Valdez worked, uncompensated, in the laundry department, organising uniform supplies orders for the five other jails.

The tents soon earned a bad reputation, according to Tom Bearup, who was chief executive officer at Arpaio’s agency until 1998. “Detention officers at first didn’t want to work there, because it was dangerous,” he says. “If there was a riot, you didn’t have a whole lot of people.” During one disturbance in 1996, Bearup saw prisoners burn some of the tents in protest.

But this didn’t stop Arpaio from gaining widespread political support for the project. “From day one I always said [to critics]: ‘Our men and women fight for our country and they live in tents, so why are you complaining when the convicted are doing their time in the tents?’” Arpaio told the Guardian.

Bearup says the project soon became a “super production” of the sheriff’s, once he realised he could rest his political career on pink underwear, chain gangs, tents and an almost cartoonish tough-on-crime image.

Michael Manning, a litigation attorney and one of Arpaio’s most ardent critics, says at times Tent City was overcrowded, making it a “horrendously dangerous environment”.

“He got away with it because people could excuse the embedded racism in his message,” Manning adds. “Because he fashioned it always as: ‘I’m going to protect you from people who are out there breaking the law and threatening your lives and property.’”

Manning won more than a dozen lawsuits tied to mistreatment and wrongful deaths at Arpaio’s jails in Maricopa County over 15 years. He won a $2m settlement over the death of Brian Crenshaw, a blind man who had an altercation with an officer inside Tent City. Crenshaw died of complications in 2003 after he was held in confinement in another jail. Another inmate, Phillip Wilson, died after a beating by other prisoners in Tent City the same year. The family refused a $1m settlement and instead went to trial and lost.

“His entire jail operation was unconstitutionally inhumane and unconstitutionally dangerous,” says Manning. Arpaio was warned about the unsafe conditions in a number of reviews about the jail, Manning says. The reports include concerns about understaffing: in a 2003 letter, the county’s risk-management department warned Arpaio that conditions needed to improve or he would pay punitive damages himself on future lawsuits from mistreated prisoners.

“People knew it was inhumane, but my Republican colleagues were so afraid of the sheriff that they let him get away with that,” says Mary Rose Wilcox, a former Democratic supervisor for 21 years to the Maricopa County board, a five-member governmental body which oversees the sheriff’s budget.

Still, the jail remained open. Presidential candidates visited it and it made international headlines, with media crews visiting from Japan and England. Tourists and the public were invited too. “It was hot in there,” remembers Kathryn Kobor, a 74-year-old woman who toured the jail in 2015, but it “wasn’t as horrific” as she had been led to believe. “You do the crime, you do the time,” she says, echoing Arpaio’s own catchphrase. Arpaio’s political career began to unravel in 2016. Many Republicans turned against him during the campaign season as he became involved in a series of costly lawsuits. Most recently and damningly, a federal judge in July found the former sheriff guilty of disobeying a 2011 order to stop detaining immigrants during traffic patrols whom he suspected of being in the country illegally, even though they had not committed any crimes.

In 2016 Arpaio’s successor, Sheriff Paul Penzone, inherited six jails and an embattled law enforcement agency under the watch of a federal monitor due to accusations of civil rights violations against Latinos. Penzone’s first step in dismantling Arpaio’s legacy was to announce the closure of Tent City – and the eradication of the mandatory pink underwear.

“This facility is not a crime deterrent, it’s not cost-efficient and it’s not tough on criminals,” said Penzone during the announcement on 4 April. The move would save taxpayers more than $4m a year, he said, after costing an average of $9m to operate.

Grant Woods, a former Republican attorney general who headed a committee appointed by Penzone to review the facility, said there was no proof that Tent City has helped prevent recidivism, as Arpaio boasted. The perception that it was tough on crime was a myth, he said.

At the time of writing, there are still around 370 men and women held in one compound of Tent City. Local civil rights groups are concerned about their health with the extreme heat advisories of the Arizona summer. They will remain there until October as part of a special programme that allows them to leave the tents to work during the day. The sheriffs office has said they will be found appropriate housing in the autumn.

On a recent visit in July, an empty tower guarded a set of courtyards covered in gravel with a patchwork of cement slabs where some of the tents used to stand. An inmate’s plastic sandal sat abandoned, scorched from pink to brown by the summer sun.

Arpaio was due to be sentenced on 5 October and faced up to six months in prison for wilfully violating a federal court order. However, last week Donald Trump threw the sheriff’s possible incarceration into doubt when it was reported he was considering a pardon for the former sheriff. President Trump reportedly told Fox News: “I might do it right away, maybe early this week. I am seriously thinking about it.” He added Arpaio was a “great American patriot” who had “done a lot in the fight against illegal immigration”.

But immigrants such as Valdez would like to see the sheriff behind bars. “He has to pay. He’ll get a taste of his own medicine,” he says. “I’ll like to see him in a little tent under the sun, wearing pink boxers, pink sandals and a pink towel.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, and explore our Archive