How to Write a History of Video Game Warfare

A journalist has assembled the first chronology of the largest war yet fought on the Internet—the Great War of EVE Online.

Imagine the Star Wars universe is real, and you live in it.

You have lived in it, every day, for the past 13 years. You’re the captain of a nimble fighter, working for money or sheer thrill; or you operate a modest mining ship, plying your trade in the nearest asteroid belt. For all that time, you have been scraping by in the final frontier—evading pirates, settling scores, and enduring the Machiavellian rise and fall of space empires. Sometimes you even pledge allegiance to a warlord.

For the more than 500,000 people who play EVE Online, this isn’t a fantasy. It’s real life. EVE Online is a massive multiplayer online game—a single environment shared by thousands of players, like World of Warcraft or Second Life—that has been in continual operation since 2003. It contains all the set pieces of space opera—moons, distant outposts, mighty dreadnoughts—but it is no ordinary video game. In fact, it is like little else on the Internet in its ability to mirror the functioning complexity of the real world.

The world of EVE, called New Eden, has devoted salesmen, ruthless technocrats, tactful diplomats, and fanatical propagandists—and, unlike most other games, almost every character, no matter how high or lowly ranked, is a real person. These thousands of players vie to support their organization and the philosophy it promulgates. And in the latter half of the 2000s, those people engaged in an enormous conflict: The Great EVE War.

That war, and the extraordinary video game that contains it, now have their first history, Empires of EVE. Andrew Groen, a journalist who’s written for Wired and Penny Arcade Report, spent the last 18 months piecing together a detailed chronology of the conflict and its three great participants. It was released this week—just in time for a new major conflict in EVE, possibly the largest to occur since the events Groen documented.

“EVE is the most real place that we’ve ever created on the Internet,” Groen told me. I’m not sure he’s wrong. Last month, we spoke about what makes EVE so emotionally important to its players and what it can tell us about the world beyond the game.This interview has been edited and condensed for the sake of clarity.

Robinson Meyer: Are you an EVE Online player? Is that how you learned of the events in the book, or did you hear about it by other means?

Andrew Groen: No, I’ve never actually been an EVE Online player, even when I was writing the book. I got to know EVE because when you’re just in the games community, when you follow games as a niche medium, you tend to hear these tip-of-the-iceberg tales about what goes on in EVE. Whispers get around of this battle that had 4,000 players in it, or this incredible Ponzi scheme someone ran that duped 10,000 people throughout the game’s history.

So a couple of years ago, I was thinking, what are the areas of video games that aren’t being serviced by journalists? And the number one thing that came out was EVE Online. And I set out to see whether anyone had ever written a definitive history of what had gone down in EVE Online, and it turned out no one had ever done it before.

When I started out, I didn’t know for sure that EVE was a game that had things like causation in it, where one event necessarily precipitates the next event. That’s not true in any other video game ever made. If you’re in World of Warcraft, and your guild is the first to kill a raid boss, that doesn’t have consequences on the rest of the world. It doesn’t change anything. The raid boss still re-spawns 24 hours later. If you die during a raid, all of your stuff comes back as soon as you resurrect.

But resources within EVE are finite. And the ability to collect those resources, and to build those resources into fleets, and armadas, and local economies—that ability is finite. So when one alliance defeats another alliance or takes over their territory, that has consequences for the power balance of the rest of the game.

Meyer: Can you give me a sense of what the world of the game is like? Like, is there finite territory in EVE, as well—when you look at the end of the star maps, are you looking at the end of space?

Groen: Basically, yeah. The way that EVE works is it’s sort of a globular cluster of stars, and all of the stars in that cluster are connected by stargates. You travel between stars only through those stargates. You wouldn’t be able to travel beyond the bounds of this particular star cluster, which is 7,800 stars total. There’s about 3,500 that can be conquered by the players.

Meyer: So half of space is tightly controlled, and the other half is open to conquering?

Groen: At the center of this globular cluster is a place called Empire Space, which is where the “lore” empires hold sway. The game’s fictional groups with all the non-player characters and AIs and things like that, they control that area of the game. That’s where you spawn into the game right when you start out playing EVE Online.

But as you get farther out, the level of law enforcement decreases. And as you get into the middling outer areas, that’s where pirates roam. There’s looser, Wild West-style law restrictions. Then, as you get even further out from that, those are the lawless territories referred to as “nullsec.” That’s where any player group can show up and plant their flag in a star system and say, “This is our system. We make the laws. We are the ones who are able to exploit its mineral wealth.”

Meyer: You said this is the only game with causality. Is it the only game you could write a history of? Are their other games that have a large, shared universe, where most of the antagonism is happening between players, and not between players and AIs?

Groen: There’s two things that make EVE Online really special. The first is that causality, where there’s finite resources and when something is destroyed in EVE, it’s gone forever. If you form an alliance of 5,000 people and you build this grand war armada of battleships, and then that fleet is destroyed, it never comes back. You are permanently weakened as a result of that. And that’s one of the ways that EVE Online is very different from any other game: Things don’t come back. It’s unforgiving in that regard.

The second is that it’s a single-server universe. If you’re familiar with games like World of Warcraft, they have 200 servers around the world, and each server is this carbon copy of the game universe. The South Koreans play on their carbon copy of the server, and the Russians have their carbon copy.

EVE Online is one server—or, well, it’s two servers. One for the Chinese and one for the rest of the world, for complicated reasons. The history that we’re talking about now is the history of the entire world playing in one shared game space. That makes EVE really, really special. It means you have these entire areas of the game where you will go into them and you can’t speak the language. You can’t negotiate with certain player groups within EVE because they only speak Russian or they only speak Swedish. You wind up with these fantastically complex governments that actually have translators and diplomats to go between these different cultures. That’s the level that a lot of these in-game groups have reached once they get up to 10,000—I think the largest one is close to 25,000 people.

There’s a terrific story about one of the most famous diplomats in EVE. He was a guy named Vile Rat, and he worked for the Goon Swarm alliance. [But in person,] he worked for the U.S. State Department as an IT expert for diplomats.

It turns into a tragic story, because he was one of the guys killed in Benghazi, in the attack on Libya. It’s an incredibly poignant moment in the history of EVE. Everybody had heard of his exploits, and some of the things he had been able to negotiate, and some of the spy stuff he had been involved in, and when he died, there were memorials all over EVE, mourning the loss of this player.

Meyer: How many of the alliances that you wrote about still exist? How fast is turnover in the game, and are there relative eras of stability between these empires in nullsec? Or are people more or less always at war?

Groen: I think to an extent, people are always fighting a little bit. But there are times when wars will break out that will make you realize, oh no, we weren’t actually at war during that period, this is what a total war looks like in EVE Online.

Probably the climax of the book that I wrote is this era known as the Great War. I think of it as a World War I-style tangle of treaties, where everyone in the game gets dragged into this huge conflict that probably included over 50,000 people. It took about two years to fully resolve.

So there is relatively quick turnover when you compare it to real-world governments, or something like that, but when you compare it to a video game, these are very stable organizations. A lot of them last for five years or longer. The chief character alliance that I follow throughout most of the book was in power from 2004 to late 2009, so that’s a pretty stable group.

Meyer: In the intro to the book, you write about how this concept of “sovereignty” was introduced in 2004 into nullsec space. It let player groups become permanent owners of stars or areas of space. And then, some time after that concept takes hold, you have a huge, huge war. Was a war like this doomed to happen from the start? In other words, as you saw something like the modern nation-state spread everywhere, did you also see problems follow that? Because all of a sudden, there’s borders and competition and other attributes that tend to force organizations into conflict.

Groen: It did introduce that political squabbling, as people quibble over borders. But at the same time, when they introduced that concept, there’s some stability to that. In the past, everybody would still try to conquer areas of space, and they would still succeed to some degree. But there was never a delineated line where you could say: This is our space, and this is your space, and you stay out of ours and into yours. Instead it was very informal. It was just like, “We are the toughest road gang on this stretch of highway, so we own it.”

I think there was some stability from sovereignty, because it allowed a lot of these governments to form. Now [EVE] doesn’t have to be just about military might anymore—now you need people to run the spreadsheets, now you need people to keep track of everything. When you officially own a piece of space, you can then rent that space to somebody else to let them exploit its mineral wealth. It probably ratcheted down some of the conflict and introduced stability.

Meyer: So what followed sovereignty was technocratic order. Once some borders got hashed out, and some alliances broke down, you can have universe bureaucrats come in and actually run some things.

Groen: That’s about the size of it. And I think around that time, you start to see some of these alliances form that aren’t as much about combat specifically, but gain strength through strength of arms rather than pure ability as pilots or fleet commanders.

Later in the book, there’s an organization called Ascendant Frontier, which really wasn’t that good at fighting at all. They had a pretty weak military. But they were so good at construction, and logistics, and building these huge armadas of ships, that when their ships got destroyed, it didn’t even matter. They would just go get three more.

So I think sovereignty allowed unique types of player alliances to form, which turned it less from a game about one-off battles into these systems where you’re watching huge, top-to-bottom logistics operations be in place, behind the battles, to reinforce the lines. And then to run those, you need very impressive leaders, who are going to give speeches to rally the workers to continue building ships or go out on the front lines of a fight that is relatively futile. And that was fascinating.

Meyer: I wondered whether it was actually uplifting or inspiring watching this. Does it create a sense that it’s a harsh, Hobbesian world, and you better pick your alliances well? Or like, even if you’re doomed by birth to live in this weaker alliance, you should give your all to it, because at least it’s romantic?

Groen: That’s certainly something you see in these leadership speeches. Leaders will know they have the short end of the stick and they’re in the weak position. And to prevent that from becoming a cascading problem—where all of your pilots realize things are looking a little grim, so they just get their stuff and leave as quickly as possible—what you’ll end up seeing is leaders giving these inspiring speeches. They’ll villainize the other side as the evil empire.

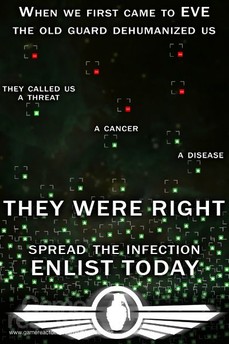

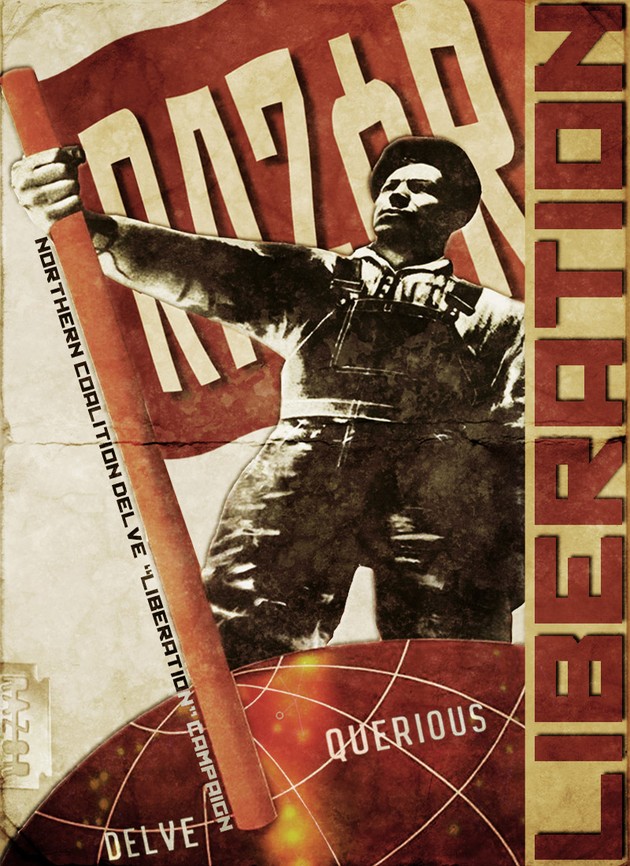

And that’s what you have to do: You have to give your pilots something to believe in. At the end of the day, no one is doomed to work for any alliance. They can, at any time, pick up their bag and leave. So inspiration and morale become these huge resources for these organizations, and that’s fun, because it means propaganda starts to matter. I have examples of these wonderful propaganda speeches, where the leaders of these alliances start talking like they’re Winston Churchill. And you get the very real sense they believe it.

Meyer: And does it retain that fun? Does it, overall, feel more like a collective human storytelling practice, and not people engaging in sad, fake war with other people for trumped-up reasons?

Groen: In the era of EVE that I write about, what makes it fun, and what makes it worth reading about, is that people believe in it. They’re not giving these leadership speeches with tongue-in-cheek sarcasm, where they seem to know they’re roleplaying. They believe so heavily in this virtual world and the mission that they’re on, and they believe so heavily in the innate evilness of their enemies.

Meyer: What are those missions? What is something that’s worth dying for—or at least sacrificing many hours of playing time for—in EVE?

Groen: The organization that I was talking about earlier, Ascendant Frontier, they had carved out an area of space in the south. They got a little too big for their britches, I think, and they ended up crafting the first Titan-class ship in EVE, which is basically the atomic bomb of EVE. Their neighboring alliance, this fascistic, aggressive alliance known as Band of Brothers, got very upset about that. And their leaders started spouting this narrative about how Ascendant Frontier must be taken down.

So Ascendant Frontier has to fight back. They’re witnessing this very militaristic organization coming into their borders and trying to shut down the way that they like to play the game, the way that they believe this game should be played, and that inspires this patriotic sense of duty in a lot of people.

In the intro chapter, I talk a little bit about how if you’re Russian in EVE, and your alliance is the only major Russian player group, you have to fight for that group. Because if that group falls apart, there’s nowhere else to go. There’s no one else to play with. You want to play with people who are Russian, you want to play with other Russians, so what are you going to do if the Russian identity in EVE Online gets destroyed? A lot of people are basically kind of fighting for their right to play the game.

Meyer: When empires get tied to nationalities, or it sounds like really to languages, do you see their rise, or their failure, get tied to the success or failure of the language-speaking actual nation states?

Groen: To an extent, you do see that, just because there aren’t a lot of alliances that come from relatively poorer nations. Those nations never started playing EVE in the first place. But if an alliance has made a footprint in EVE like the Russians, I doubt you’d be able to notice a diminishing Russian presence inside EVE because the ruble is falling or something like that.

Meyer: Although data scientists, I think, could have a lot of fun.

Groen: Oh man, speaking of that, I met these two guys from the University of Ghent who created a computer model that shows what happens to economic prices in certain parts of EVE, depending on whether or not there are battles going on nearby.

In these areas where a lot of ships are being destroyed, you would expect to see the price of materials skyrocket, because everyone’s trying to build new ships and new fleets. But what they found was that, in areas where a lot of ships are being destroyed, the prices go through the floor, because everyone in that region of space starts liquidating everything. There’s an invading alliance coming, and they’re trying to get their stuff out the door as fast as possible, to make sure their stuff doesn’t get taken or conquered. They said this is similar to what you see in the real world. In pre-war Germany, the price of gold dropped through the floor because everyone was trying to liquidate their belongings and get out of the country. …

EVE is the most real place that we’ve ever created on the Internet. And that is borne out in these war stories. And it’s borne out because these people who—you find this over and over again—who don’t view this as fictional. They don’t view it as a game. They view it as a very real part of their lives, and a very real part of their accomplishments as people.

There was one quote that a guy who—I can’t imagine this quote in anything but a deep southern Georgia drawl, because that was how he talked—he said, “this wasn’t a game for us. This was our home. They were our enemies. We hated them—and not in a virtual way. We hated them.” This dude is telling me that they reviled their enemies. There’s something very real in how people respond to [EVE], which blends the line between what we consider to be a virtual and a real space.

Meyer: Did you see the politics in EVE reflecting global political ideologies? Do you see battles happening in these empires, disputes, over how things should be taxed or how free should trade be, for instance?

Groen: I don’t think you would find conflicts about things as small as how taxes should be structured—usually what kicks it off is that someone is using a star system across their borders. But you do see things that are ideologically inspired, and it usually comes down to how you should treat the game.

Meyer: What are two conflicting philosophies of gameplay?

Groen: The main organization I talk about in the book, the Band of Brothers—it’s hard to decide whether they’re more of a communist organization or more of a fascist organization, because they literally confiscated all of their members’ goods when they are accepted as a member of Band of Brothers. And the leader of that alliance would control them and tell them where to go.

The main conflict in the second half of the book is between them and an organization called Goonswarm—or rather their parent alliance, an organization called Red Swarm Federation. The goons are from SomethingAwful.com, and they’re very, I’d say, Internet jovial. They like to troll, they like to take people down a notch who were taking themselves too seriously. They came into EVE and one of the first things they saw was this organization taking itself incredibly seriously. And they started to mock and poke that sleeping giant. That’s where one of the biggest wars in EVE’s history kicks off. It becomes this unstoppable conflict, just sort of a boulder-rolling-down-the-hill sort of thing.

Meyer: And that was the organization that Vile Rat was a part of?

Groen: Yeah, he was a goon. It’s one of those things that you find when you start looking at EVE Online for long enough—the people who play, and the people who succeed at the game, are genuinely brilliant. When you talk to the leaders who run these organizations, you’ll ask them casually while a call is wrapping up, so what do you do for a living? And this one woman said, oh, I run a nuclear reactor up in Portland. Another guy was like, oh, I run an international shipping and logistics company.

I know for sure—no one will tell me who it is because it’s kind of a secret—but I do know that, somewhere out there, there is a corporation in EVE that is run exclusively by Fortune 500 CEOs.

Meyer: How do you put together a history of a world where the first draft is all propaganda?

Groen: It’s kind of a classic historical problem. A lot of times, when people lose wars, and when leaders lose their organizations, they quit the game. Part of the reason why EVE can be so shrouded in propaganda is that those players do go away, and then they no longer maintain their stature in the community or the credibility to tell the history of what happened to them and their organizations. In EVE, you very much have a winners-write-history sort of problem.

The way you counter that is by doing the journalistic legwork to go back and find those people who played the game 10 years ago, or 15 years ago, and get their side of the story. And find their old documents and old resources that they were using to document their history. I think I interviewed about 70 people for this book. I’m sure you sympathize with the difficulty of finding a source when all you know about them is the alias with which they played a video game 12 years ago.

Meyer: Is there any game record of what these battles look like?

Groen: Not perfect ones, and mostly it’s only from post-2007. There’s a website called Dot Lan, that has certain types of records. It’ll tell you how many ships were destroyed in a system on a certain date, or it’ll tell you when a certain alliance conquered which star systems. So you can find a lot of little data points which, if you know what to look for, you can paint into a larger picture of what was happening at the time.

Meyer: Were there journalists, or, like, truth-finders, wandering around in-game?

Groen: Not specifically. It’s very rare to find journalists who can get into these organizations and gain their trust and still remain impartial. A lot of people who were writing down accounts were incredibly partial. I include one or two of them in the book, just to show, here’s how completely over the top these people viewed themselves.

Meyer: Did doing all this research make you want to play the game, like it made you really want to get into it? Or was writing the book all the exposure you needed?

Groen: It took me a little while to understand this, but I think that I was playing EVE while I was doing this research. I was just playing it in a way that no one had ever done before. This was my niche in the community, this was how I contributed to the community. I don’t fly my spaceship through the darkness of EVE Online, and go past the stars and whatnot, but EVE is the only game I’ve found where it does feel like you can play the game without ever logging in.

And that has been borne out by some of the leaders in the game’s history—they’re so busy running their alliances, they don’t have time to log in and actually play the game. So they don’t. They’re playing the game through Google Docs, spreadsheets, IRC channels. They’re holding meetings with all the other leaders; they’re having diplomatic conferences in chat rooms.

Meyer: Do they need to maintain embodiment in the game at all? Did leaders need to maintain an avatar in the world of stars and fighters in order to govern?

Groen: No, there are people who have just stopped logging in. They met with their lieutenants outside the game, and those lieutenants were their presence in the game. The leader of Goonswarm is famous for never really logging in anymore. I think it’s been years since he logged in.

Meyer: Do different tactical strategies emerge at all?

Groen: You definitely start to see different philosophies arise. Leaders start to figure out that they don’t have to fight their enemies. And if they don’t, they can start to chip away at their enemies’ morale because those players have showed up to fight. They’ve showed up to participate in a battle. So if you don’t give them that battle, if you don’t show up unless you absolutely have to—in the community they would call it “blueballsing” the enemy fleet. These players have showed up, they’ve given up six hours of their Saturday, and they didn’t even get to fight. And that has profound implications for the morale of a fleet, how well they’ll listen to their commanders, and whether you can get those players to show up next time.

Meyer: So the tactic here is to act like there will be a battle and then not show up?

Groen: You basically don’t want to give them anything fun. Deny them fun at any cost. If they show up to destroy one of your starbases, don’t defend it. Let them show up and shoot at the starbase and slowly destroy it over the course of three hours. It’s kind of ruthless in that regard: “We’re just not going to play the game.”

Meyer: So it sounds like one of the key resources here, and one of the things being fought over, is boredom.

Groen: Oh yeah, absolutely. Something that I found formed very early on in EVE was the understanding among certain leaders was that people will follow you, even if they don’t believe in what you believe in, simply because you’re giving them something to believe in. You’re giving them a reason to play this game. You’re giving them a narrative to unite behind, and that’s fun. It’s far more fun to crusade against the evil empire than it is to show up and shoot lasers at spaceships.

One of the things that I think was being fought over in the Great War was the ability to form narratives like this. The organization of Band of Brothers was very, very serious. They had this Winston Churchill vibe going on, where they want to stand on the stump and give a massive war speech and announce their invasion in the character of space dictator. The goons, on the other hand, are jocular. They don’t hold to that sort of thing. By the end of the book, when the Goons win and take over, a lot of that stuff falls by the wayside. They bring a lingua franca to EVE that is, “You should not take this too seriously.”

Meyer: You said it was the realest place online that has ever been made. It feels like all the things that people got excited about with Second Life, or any of those previous virtual worlds, actually exists here.

Groen: Second Life was hyped to bring out the personal ideal of a virtual space, while EVE actually brings out the collective ideal of a virtual space. What happens when humans are able to coordinate in groups of tens of thousands inside a virtual space? It hits on the same theme.

This is what I want people to understand and take away from the whole thing. Not just that this was some weird thing that happened in a video game, but that this was a really notable part of the history of the Internet. It’s one of the first times we can point to something and see an ideologically fueled conflict taking place on the Internet between tens of thousands of networked individuals. These wars and these battles are probably the largest conflicts in the history of the Internet. There’s something deeply exciting and fascinating about that—what wars actually look like when you fight them online. It is, in a weird way, a harbinger of maybe how things may work in the future.