Inside LAX's New Anti-Terrorism Intelligence Unit

If the airport’s experimental team succeeds, every critical infrastructure site in the world might soon have its own in-house intel operation.

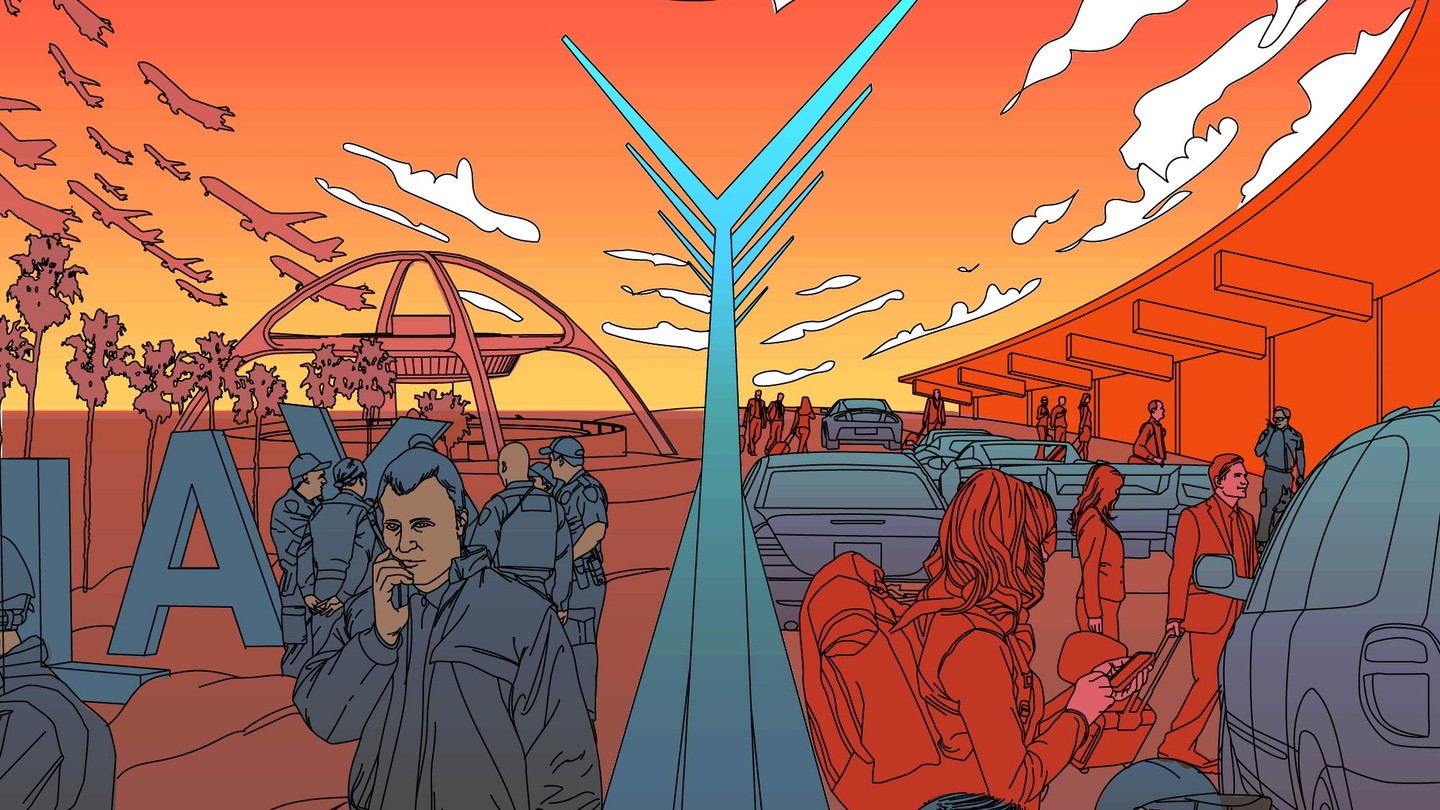

No one paid the car any attention as it crept forward through morning traffic at LAX. Travelers wandering the arrivals area with their smartphones out, hands held up to block the sun, never even gave it a second thought.

Then the driver swerved, accelerating onto the sidewalk in front of Terminal 7. It ran over bags, flattened signage, and collided with pedestrians too slow to jump out of the way. Within seconds, before anyone had a chance to respond—to help the victims, to call 911—the driver detonated a homemade bomb hidden inside his car trunk.

The resulting explosion obliterated the front of the terminal, leading to a partial building collapse, and a catastrophic fire began to spread toward the gate area. The window-shattering blast was heard throughout the airport as black smoke, visible for miles, lifted in a pillar into the sky. Dozens were killed instantly.

Suicide car bombing had come to LAX.

* * *

In the summer of 2014, Anthony McGinty and Michelle Sosa were hired by Los Angeles World Airports to lead a unique, new classified intelligence unit on the West Coast. After only two years, their global scope and analytic capabilities promise to rival the agencies of a small nation-state. Their roles suggest an intriguing new direction for infrastructure protection in an era when threats are as internationally networked as they are hard to predict.

McGinty, 54, is a retired D.C. homicide detective now living in Pasadena. McGinty’s tenure in the nation’s capital, where he attained the rank of detective first grade, coincided with that city’s worst era for crime, in the early 1990s, when it was known as the murder capital of the United States. A Marine veteran who was stationed variously in Okinawa, Kosovo, Honduras, and the Mediterranean, and, as a reservist, served in the second Gulf War, McGinty is quiet, keeps his hair shorn close to his scalp, and bears a slight resemblance to actor J.K. Simmons.

While he was working the murder beat back east, McGinty also applied for and received a top-secret clearance. “I’d done everything I’d wanted to do in homicide,” he explained to me. What’s more, he said, he had come back from his reserve deployment in Iraq to find his old squad broken up, his former partners gone. It was time for something new. Obtaining a security clearance helped pave the way for him to become a liaison between D.C. police command staff and the National Counter-Terrorism Center in Northern Virginia. There, one of his core responsibilities was to review classified overseas intelligence reports, detailing threats that might target the D.C. area. It was this experience that set the stage for his career’s unexpected second act at LAX.

His partner Sosa, 37, graduated with a degree in international relations from Boston University in May 2001. Trilingual in French, Spanish, and English, Sosa did not immediately know what sort of career to pursue. As a student, she had often flown cross-country from Boston to Los Angeles to visit her father, who works for the airline industry. When the 9/11 terrorist attacks occurred only four months after she graduated, Sosa realized that one of the planes, hijacked by ringleader Mohamed Atta, was on the same Boston-to-Los Angeles route Sosa herself had flown so many times before.

No longer confused about what to do with her degree, Sosa was moved by the attacks to apply for a federal intelligence job. Six months later, she disappeared into the labyrinth of U.S. intelligence, toiling as an analyst over the course of the next decade in both Florida and D.C., where she was often a youthful, even glamorous presence in a world of fluorescent lights and office cubicles. Her move out west to Los Angeles was not only professionally motivated: Sosa wanted to live near her family again, to ensure that her now 7-year-old daughter could grow up in the company of her grandparents.

As McGinty describes it, their current operation falls somewhere between a start-up and a think tank. Because she came from an intelligence background, Sosa had an eye for big-picture narratives; McGinty’s 25 years as a street detective and war veteran gave him tactical insights and a deep knowledge of police culture. Together, the two of them have brought classified in-house intelligence analysis to one of the world’s busiest airports, augmenting traditional beat-police operations with an investigatory agenda previously only associated not just with a federal agency but with the power and reach of a sovereign nation.

In his September 2016 cover story for The Atlantic, Stephen Brill suggested that infrastructure’s outsize political influence today has only been amplified and accelerated by the country’s ongoing reaction to the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Under the moniker of “critical infrastructure protection,” energy-production, transportation-logistics, waste-disposal, and other sites have been transformed from often-overlooked megaprojects on the edge of the metropolis into the heavily fortified, tactical crown jewels of the modern state. Bridges, tunnels, ports, dams, pipelines, and airfields have an emergent geopolitical clout that now rivals democratically elected civic institutions.

Sosa and McGinty’s unit is LAX’s attempt to reinvent itself as a player on the international intelligence stage. Their work promises to propel the city’s aging airport to the forefront of today’s conversations about what it means to protect critical infrastructure and, in the process, to redefine where true power lies in the 21st-century metropolis.

* * *

The car bomb that decimated Terminal 7 shut down LAX for nearly a week and led to a nationwide terror alert. Flights around the world were affected. Incoming planes had to be rerouted to other regional airports, causing knock-on problems elsewhere. Cargo losses at LAX alone were estimated at more than $100 million per day. Over the course of the next week, the death toll continued to rise as victims succumbed to their injuries in the overwhelmed emergency rooms of local hospitals.

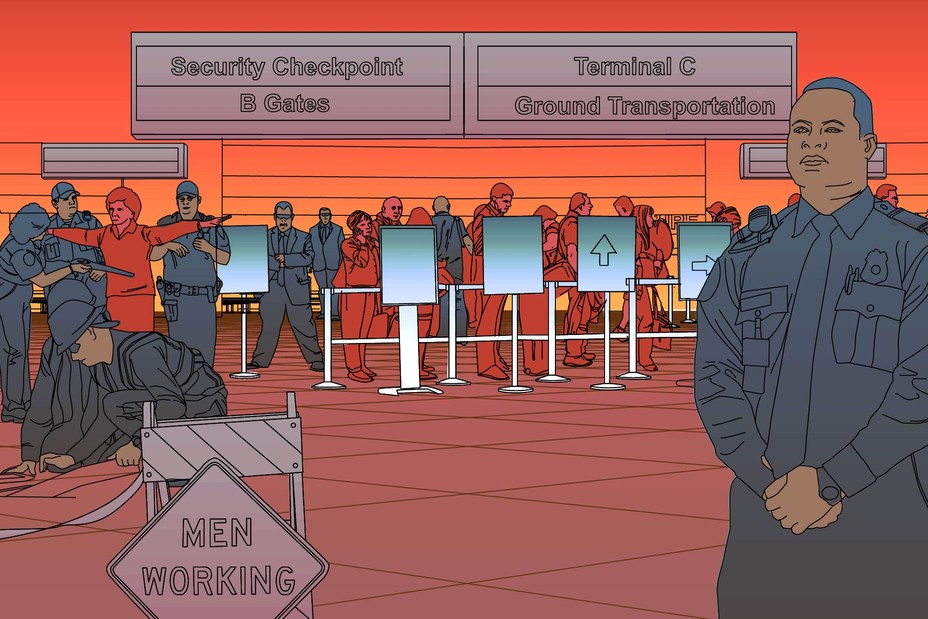

The attack was a sobering but—thankfully—fictional scenario, part of an emergency tabletop exercise held in a conference room deep inside the Westin Los Angeles Airport Hotel. The meeting was what’s known as an Aviation Security Contingency Plan Exercise, or AVSEC. Workers in airport traffic control, Homeland Security, Fire Department, Transportation Security Administration, and police uniforms joined colleagues from the FBI, multiple international and domestic airlines, and nearby airport hotels to discuss the latest in threat prevention. The exercise occurs once a year, always with a different plot. There have been car bombs, hijackings, mass shootings—an ever-growing catalog of speculative catastrophes, all carefully studied and dissected for their training or tactical value.

The idea of bringing McGinty and Sosa to Los Angeles can be traced back to Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa’s administration. In November 2010, Villaraigosa assembled a Blue Ribbon Panel to assess the state of airport security in and around Los Angeles. There was a general—and, as the panel confirmed, justified—fear that the region’s airports were not prepared to respond to a terrorist threat of any nature, let alone to something on the scale of 9/11. The group’s final report was released seven months later, in June 2011, and it included 162 pages of specific recommendations for the airport authority to implement as quickly as possible.

One of the commission’s key suggestions was that Los Angeles World Airports, or LAWA, the umbrella organization that controls not just LAX but a smaller regional airport in Van Nuys, “should consider creating the position of Director of Intelligence.” The person in this role “would proactively gather and share counterterrorism intelligence,” and he or she would do so not only with the region’s many airports, from LAX to Palm Springs, Van Nuys to San Diego, but also with federal—even, if necessary, international—law-enforcement agencies. To assist with this, the report suggested, the airport’s future director of intelligence should also hire “a staff focused exclusively on gathering and analyzing intelligence regarding terrorist threats.” LAX would no longer be dependent on secondhand reports.

Ethel McGuire, a senior LAWA official and member of the Blue Ribbon Panel, took this advice seriously. In the end, she hired not just one but two intelligence analysts for the job: Anthony McGinty and Michelle Sosa. McGuire was impressed by the complementary approaches that McGinty and Sosa employed—so she rewrote some budget lines and grabbed them both.

McGuire herself came to LAWA, where she is now assistant chief, after a full career at the FBI. She was, in fact, one of the very few female African American agents in the Bureau’s history. Her daughter is also now an FBI special agent, making them the only mother-daughter duo ever to serve in the FBI simultaneously.

McGuire is soft-spoken, with elegantly cropped hair and a helpful, even grandmotherly, demeanor. She and I met in person at the AVSEC exercise, during a break from discussions of terrorist car bombs, radiation fears, and terminal fires. Sosa and McGinty’s work is still experimental, she emphasized. “I didn’t know exactly how this would work,” McGuire said. After all, when she first got to LAWA in 2010, finding good intelligence about airport-directed threats was nearly impossible. “But I was like: Look, this was my former life. I know stuff happens at the airport! We’ve got to be able to provide something more if you want to protect this critical asset.”

LAX is a city within a city. At more than five square miles, it is only slightly smaller than Beverly Hills. More than 50,000 badged employees report to work there each day, many with direct access to the airfield—and thus to the vulnerable aircraft waiting upon it. More than 100,000 passenger vehicles use the airport’s roads and parking lots every day, and, in 2015 alone, LAX hosted 75 million passengers in combined departures and arrivals.

LAX is also policed like a city. The airport has its own SWAT team—known as the Emergency Services Unit—and employs roughly 500 sworn police officers, double the number of cops in the well-off city of Pasadena and more than the total number of state police in all of Rhode Island.

“Not only do you have the operational component,” McGuire said, “but you have all the policing—and policing is so different from intelligence gathering. What I wanted to do was to really heighten or enhance the intelligence portion. It is so impactful to how you police, why you police, where you police, and everything that you do in combating a terrorist threat.”

For their work to have any real tactical value, McGinty and Sosa need to assess a world that exists far beyond the perimeter of LAX. “This is global,” McGuire said. “We’re an international airport. We have about a hundred different countries flying here. If you stop traffic at LAX, it has an immediate global impact on aviation; if LAX shuts down, it immediately affects a hundred other countries.”

On a cloudless, 76-degree autumn day, I was picked up in an armor-plated Ford Interceptor driven by LAWA police officer Tia Moore. McGinty rode quietly in the back seat, phone in one hand, small notebook open on his knee.

“LAX attracts people who have a political agenda,” McGinty said. We were heading out onto the airfield for a combined introductory tour and routine daily patrol, where we drove for miles among the roots of jetways and towering international aircraft. A heat haze coming off the tarmac gave everything an otherworldly, almost oceanic shimmer. We passed baggage trucks and other security vehicles, and stopped at easily missed intersections marked on the ground with colored paint. With most vertical obstructions banned—lest they endanger the aircraft—the landscape has to be read on the ground, as if driving through a two-dimensional diagram five square miles in size.

Think of the so-called “Millennium Bomber,” McGinty told me as we drove on. He was arrested trying to cross the U.S./Canadian border back in December 1999 with a car full of explosives—and his stated goal had been to bomb LAX. Or think of the man who targeted Israeli airline El Al in a combined knife and gun attack at the airport on July 4, 2002. Or the unemployed anti-government conspiracy theorist who drove to LAX in November 2013 for no other reason than to shoot and kill a Transportation Security Administration (TSA) agent.

On the other hand, dramatic security events at the Los Angeles airport sometimes border on the absurd. In August 2016, a man dressed as Zorro, carrying a plastic sword, triggered an armed response by LAWA police; unfortunately for Zorro, his appearance coincided with panic over a possible active shooter somewhere else in the airport. The resulting near-stampede threw LAX into chaos, with passengers and employees alike fleeing through security doors and assembling outside near the runways. At the AVSEC exercise, the episode was alternately referred to as “Zorro Day” and the “Zorro Incident,” not without stifled laughter.

“You never know what you’re going to get,” McGinty said.

We stuck as close to the airport perimeter as we could, looking out at the black windows of nearby hotels, through which someone, of course, could also be watching us. McGinty explained that the process of gathering useful intelligence includes meeting with those local hotel managers to discuss potential threats. “Our job is to go beyond the perimeter,” he said. There might be a suspicious guest filming airplanes from his or her hotel room, for example, or someone setting off a hotel’s rooftop alarm. They might just be going outside for a smoke—or they might be trying to shoot down one of the many planes flying unnervingly low overhead.

Stacey Peel, a globally recognized expert on the security implications of airport design, would agree with this assessment. She told me that even the best-designed aviation facilities still have serious security flaws, especially if, for example, their runways are surrounded by badly managed hotels with direct views of the airplanes. Approach roads, parking lots, green spaces—let alone local crime statistics—all help to define an airport’s threat profile. Each profile, much to the consternation of security professionals, is resolutely, frustratingly unique.

Peel currently works in central London, where she is head of the “strategic aviation security” team at engineering super-firm Arup. She explained that every airport can be thought of as a miniature version of the city that hosts it. An airport thus concentrates, in one vulnerable place, many of the very things a terrorist is most likely to target. “The economic impact, the media imagery, the public anxiety, the mass casualties, the cultural symbolism,” Peel pointed out. “The aviation industry ticks all of those boxes.” Attack LAX and you symbolically attack the entirety of L.A., not to mention the nerve center of Western entertainment. It’s an infrastructural voodoo doll.

As the tour continued, McGinty stressed that even someone heading toward LAX in a taxi, acting strangely—perhaps holding unusual luggage, talking about God and bombs—needs to be on their radar. Does the driver have a way to contact airport security without tipping off the passenger? Will LAWA police lose track of the taxi amid the hundreds of other vehicles visiting the facility that day? Is the person inside even a danger?

We eventually reached a distant, all-but-silent corner of the airfield where suspected bombs are dealt with. McGinty pointed my attention down to a number of blue grids are painted on the concrete. These indicated spots where baggage could be detonated. He then noted a massive blue circle surrounding it all, a shape so large I, paradoxically, would not have noticed it. This circle, visible on Google Earth, marks the outer perimeter within which an entire aircraft could be parked during a bomb scare.

Of course, securing LAX doesn’t always involve big-ticket threats like this—or, indeed, even like Zorro Day. Officer Moore explained that she has responded to plenty of incidents of sheer stupidity, including stray pets, from dogs to birds, going wild in the terminals. A confused woman “off her meds” caused a seemingly endless series of car accidents in the passenger drop-off area. One night, two people caught sneaking a drink in a restricted area fled at great personal danger toward an active runway until Moore herself ran them down on foot. As trivial as these sound, any one of these events could have been a distraction for a larger terrorist incident; McGinty and Sosa must pay attention to every one of them.

While we were talking, I noticed a field of sand dunes and empty streets at the western end of the airport. There used to be a suburb there. A wealthy coastal enclave called Surfridge was acquired through eminent domain by the city of Los Angeles in the 1960s. Following a referendum in 1965, Surfridge was slowly dismantled in the name of airport safety, leaving behind nothing but uninhabited streets. The area is now officially a butterfly preserve, its cracked pavement nonetheless used by LAWA police as a convenient site for tactical-driver training school and simulated chemical attacks.

The ghostly remains of Surfridge also present an unusual security risk. As we drove through a padlocked gate, McGinty noted that various systems of alarms and sensors ring the now-dead neighborhood, a place where not a single house remains but where retaining walls and old water pipes are still visible sticking up from the sandy ground. The views of the sea are incredible.

If an alarm goes off, it could just be kids sneaking in to smoke pot, he pointed out, or it could be something far worse. He mentioned the possibility of a terrorist group or cartel-affiliated gang smuggling shoulder-fired missiles into the city with the goal of shooting down planes at LAX. “The dunes,” as McGinty referred to Surfridge, would be an ideal location for this.

Indeed, the outer edge of LAX is one of the most interesting parts of the entire airport. I spent several hours that day touring secure construction sites; an emergency-operations center with clocks set to local time in Singapore, Sydney, London, and Moscow; a sprawling fuel depot, connected by underground pipelines all the way to Long Beach; and a closed-circuit television (CCTV) hub, but it was this transition zone between LAX and the rest of the city, where the civilian world hits the secure one, that emerged as perhaps McGinty’s greatest source of concern.

Of course, the true shape of the airport’s perimeter is invisible to the unaided eye; it is much more high-tech than mere fences and automotive patrols. Among other things, McGinty added, new tracking software is being tested to keep tabs on area drones. What’s more, with revised airspace regulations and new technological options, such as “geofencing” and GPS jamming, future neighbors might find that their shiny new toys literally cannot fly within a mile or two of the airport. Why tear down the next Surfridge, in other words, when you can simply reprogram its airspace?

LAX is currently embroiled in a multibillion-dollar “modernization” program. When McGinty and I got out of the car to wander on foot through a maze of badge-accessible doors, security checkpoints, and active construction sites, the true scale of the disruption became clear. McGinty compared it to a puzzle. “You’re running an airport and you’re building an airport at the same time,” he said. We stepped around piles of drywall and out of the way of errant forklifts. The oldest terminals are being upgraded; an entire new facility is being built outside the perimeter fence to concentrate car-rental returns; and there is even a seven-story automated “people mover” currently awaiting construction.

An innovative private terminal to be built on the southeastern edge of LAX is set to join the turmoil. The Private Suite at LAX, as it’s known, will be a high-priced VIP facility for travelers who would like—and who can afford—greater anonymity. Whether you’re a movie star or foreign royalty, the Private Suite is where you can sip your champagne (and drop off your luggage) isolated from the gaze of both fellow travelers and L.A. paparazzi.

The Private Suite is the brainchild of security consultant Gavin de Becker. The silver-haired de Becker is the author of, among other things, The Gift of Fear, a 1997 book that advocates respecting your instinctive reactions to dangerous situations and people in order to protect yourself from impending violence. Despite his focus on security, and with a well-known expertise in protecting clients from assassination, de Becker is a critic of what he calls “Fort Apache architecture,” the aggressively unfriendly, even anti-civic design tendencies that result in foreboding expressions of defensiveness and paranoia. Security, he believes, can be achieved through more subtle and aesthetic means.

As anyone who has ever watched TMZ or clicked on a YouTube video of a celebrity arriving at LAX has seen, it is obvious that the airport, as it currently exists, has a celebrity problem. This is not just an issue for the over-inflated egos of VIP travelers; it is an irritation for other, less gilded flyers, and it can be an enormous headache for airport-security teams. Massive crowds of closely packed, emotionally agitated fans and photographers do not always make for safe public gatherings. The Private Suite at LAX aims to sidestep all this by literally removing VIP travelers from the equation.

The Private Suite is located three miles away from the main terminals, although it is still within the confines of the airfield. Accessed via the Imperial Freeway, it poses almost no traffic concerns and benefits from a location that makes paparazzi photography—not to mention sniper fire—effectively impossible. Travelers need not be flying a private aircraft to use the new terminal; they can be escorted from the security and comfort of their suite, directly to a commercial jet. Even their TSA inspection will take place in private. De Becker was inspired, at least in part, by the Windsor Lounge at London’s Heathrow Airport, another VIP terminal where the cost of access currently hovers around $4,000 per person per flight. Many of de Becker’s existing clients already use the Windsor Suite, he explained to me, and it seemed like a no-brainer to try something similar in Los Angeles.

I met with de Becker in a secure office complex whose location I agreed not to reveal; de Becker was physically off-site that day, however, so we spoke through an encrypted video link. The interiors are soundproofed and include a shooting gallery, an entire airplane fuselage used for live training exercises, and an architectural mockup of the future Private Suite at LAX. Signed photos from film stars and U.S. presidents, thanking de Becker for his service, line the walls. The sign outside the complex is deliberately misleading; you could walk past de Becker’s false-front office every day and never guess that it is a laboratory for, among other things, preventing assassinations.

“LAX is arguably the number-one terrorist target in the United States,” de Becker began, “and certainly the number-one aviation target.” By removing what de Becker calls “high-risk, high-profile travelers” from the existing gates and terminals, a significant additional target of potential violence and a substantial source of logistical disruption can be eliminated at a stroke. As I sat near a window overlooking a soundproof room stocked with high-power rifles and a bullet-riddled SUV, de Becker was keen to emphasize to me that his project is not intended as a luxury experience for the 1 percent. Its aim is to provide a vital security service for everyone who flies into and out of LAX. “Our mission is to prevent commotion,” de Becker said. “We want to peel those travelers off the main terminal and make it a far easier intelligence and security job to manage.”

Of course, one side effect of the Private Suite is that it will concentrate high-value targets—from pop bands to hedge-fund managers—in one location, raising the possibility of future spectacular attacks; but, De Becker emphasized, the Private Suite is not open to public visitation or even to public view. This fact alone offers an immediate buffer, an example of what he calls “white space,” the protective quarantine something needs in order to maintain operational safety.

It is also a project that LAX is uniquely qualified to host, de Becker added. Precisely because of the airport’s precarious mix of high-risk travelers, its valuable global cargo, its constricted urban location, and its tens of millions of annual users, LAX is in an ideal position to innovate—because it must.

As LAX goes, in other words, so go other airports around the world—at least that’s what de Becker hopes, as the Private Suite has yet to open for business. When it does launch in 2017, however, its effect on security will be instantaneous, as the new terminal promises to drastically rearrange the airport’s internal dynamics, like a cell splitting in two. As McGinty pointed out to me, “The environment always shapes the response”—and this is never more true than when the environment itself is constantly shifting.

LAWA’s intelligence headquarters is located in an unremarkable gated complex, tucked behind a cinderblock wall on a dead-end street off Sepulveda Boulevard. The famously close approach of passenger jets supplies a near-continuous roar, reminding everyone of what they’re there to protect. This is where McGinty comes to work each day. (Sosa spends most of her time at the Joint Regional Intelligence Center, a straight shot east on the freeway in Norwalk.)

McGinty leads me through a series of badge-accessible doors into a low-ceilinged room filled with cubicles. There are model airplanes and spare security uniforms, as well as a small stack of orange spiral-bound notebooks on one of McGinty’s bookshelves. I asked about them.

He pulled a few down from the shelf to show me. “My wife is Japanese,” he explained. Every once in a while, the two of them will go to the downtown branch of Kinokuniya, the stationery and literature megastore roughly equivalent to a Japanese Barnes & Noble, where McGinty likes to buy a particular brand of notebook. Falling back on old habits from his days with the D.C. police, he said, he uses these to keep notes and track larger research questions for every day on the job.

McGinty has clearly held onto his detective roots: In one of his desk drawers was a binder stuffed with old case files—or “case jackets,” in police parlance—that he had brought with him from D.C. These included page after page of former investigations, including gang shootings and serial killers. McGinty also worked internal affairs, he said, where he served briefly in a police corruption unit, pursuing cops who, among other things, had been openly profiting from a prostitution ring.

In one sense, LAX is a giant speculative crime scene whose diffuse borders and international suspects require more than just foot patrols and CCTV. While McGinty cagily avoided any questions about specific threats he and Sosa might currently be investigating, we touched upon everything from stray shoulder-fired missiles and South American terrorist groups to disgruntled cargo employees and the latest issue of the ISIS magazine Rumiyah. Elsewhere on his desk were guides to the science of crowd control, an encyclopedia of airport operations, even a pamphlet or two about extremist networks, including one on how to recognize and interpret white-nationalist tattoos.

To protect LAX, he said, you have to know about all of this—riots and lone-wolf terrorists, car bombs and foreign dignitaries. It was about asking the right research questions and understanding the true global context for what might appear, at first, to be a local event.

Greg Lindsay is coauthor of the 2011 book Aerotropolis: The Way We’ll Live Next, written with University of North Carolina business consultant John Kasarda. Seen through Lindsay's eyes, aviation logistics takes on near-psychedelic dimensions. When someone looks at a map of the world, he or she might take in superficial details, like the outlines of nation-states, but Lindsay sees tax-free supply-chain hubs, special economic zones, and transnational land deals. Individual airports, he pointed out, are complexly knit together through global-service contracts and preferred air routes that often defy straightforward geopolitical explanations. What’s more, the value of consumer goods that pass through the LAX-to-Tokyo or LAX-to-Shanghai air corridors often exceeds the GDPs of many nation-states—yet those invisible routes, despite their outsize economic influence, don’t show up on world maps.

The fact that an airport such as LAX would begin to realize its true power and economic stature in the world is not at all surprising for Lindsay—nor, of course, is it news to anyone that airports are increasingly terrorist targets. A piece of infrastructure turning into its own intelligence-gathering apparatus, Lindsay suggested, is just “the natural trickle-down effect of when, after 9/11, the NYPD expanded its own intelligence efforts, deciding that the FBI, CIA, and Homeland Security were simply not good enough. They had to project their own presence.” More to the point, they realized, like LAX, just how much there was to protect—and how badly other people wanted to destroy it.

Today’s threats, whether terrorist or merely criminal, are increasingly networked and dispersed; it only makes sense that an institution’s response to them must take a similar form. It might sound like science fiction, but, in 20 years’ time, it could very well be that LAX has a stronger international-intelligence game than many U.S. allies. LAX field agents could be embedded overseas, cultivating informants, sussing out impending threats. It will be an era of infrastructural intelligence, when airfields, bridges, ports, and tunnels have, in effect, their own internal versions of the CIA—and LAX will have been there first.

Indeed, the LAX model of in-house analysts—such as McGinty and Sosa—working with classified intelligence material, has already become an objective elsewhere. Other airports are watching. Christian Samlaska, the senior manager of aviation security at the Port of Seattle, is currently working on a similar initiative, he told me. “This is something we want to adopt,” he said. Samlaska went on to explain that SeaTac—the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport—is putting substantial resources into full employee screening in order to combat the ominous possibility of an insider threat. The next wave of attacks could very well come from radicalized workers with security access.

“Our new norm is the unknown,” said McGuire, the LAWA official who hired McGinty and Sosa, as she and I wrapped up our conversation. McGuire is worried that the calculus for anticipating certain kinds of attacks could change, and she feels an urgency for airport intelligence to keep up. “Our new norm is: What’s next?” McGuire added after a pause. “And that’s how it shouldn’t be.”

Case Files

Although Anthony McGinty and Michelle Sosa declined to provide information about specific criminal cases or terrorist plots that they have tracked while working at the airport, several hypothetical narratives emerged from my interviews with law-enforcement authorities at LAX. The following scenarios are not examples of actual events that have taken place, or of real threats that have been averted, but are instead meant as provocative fictions similar to the AVSEC exercise described in this article. Nonetheless, these are the kinds of scenarios that Sosa and McGinty were hired to protect against every day.

Taxi Driver

A local yellow-cab driver picks up a passenger in Westwood who asks to be taken to LAX—but the customer is carrying a backpack from which odd-looking wires protrude and he has begun making highly suspicious comments into his cellphone. The driver manages to notify airport authorities without the passenger realizing it—but Los Angeles police officers have lost the taxi in traffic. The clock is ticking; the car is only blocks away.

Internal Affairs

Someone with secure access to an airplane has been helping to ship contraband goods. As McGinty and Sosa explained to me, passengers smuggling drugs, weapons, and cash through LAX is unnervingly common—but this is a particularly ominous case, because it reveals an insider threat. A member of an aircrew, authorities learn, has been paid to stash “something” on an outbound plane; the worker appears to have been duped into loading an explosive device into the cargo hold. Finding which airplane—as well as the network of airport workers responsible—is urgent.

Age of the Wolf

Two Iraq War veterans from eastern Oregon, already known to authorities for expressing vigorous support for white-power groups on social media, have stolen so-called MANPADs (Man-portable Air Defense Systems) from a National Guard armory in central California. On Tuesday morning, they are spotted in the Los Angeles suburb of Palmdale. That Friday night, there is a perimeter breach in the dunes behind LAX, and a van is parked in the vicinity with plates that LAWA police have traced back to a militant neo-Nazi. Many international flights are already on the runway, lined up for takeoff.

Hotel California

A Moroccan woman staying at a hotel near LAX leaves a video camera mounted on a tripod in her hotel room while she is out for the day. Although the camera is turned off, the housecleaning crew believes that she has been filming takeoffs and landings. They notify their manager. Federal authorities soon learn that the guest’s overseas associates once appeared on an FBI watch-list (although they have since been removed). Is the woman a film buff, an aviation enthusiast—or an imminent threat?

The Arrival

A logistical mix-up overseas means that, with less than three hours before arrival, federal authorities learn that a notorious, widely hated member of a European organized crime family is on his way to LAX—and, it is feared, his presence in the city will not go unnoticed by local rivals. Airport authorities need immediate intelligence on whether or not someone might try to confront and even kill him within the airport; worse, they now have only two hours to gather this information and put it to use.

Fatal Attraction

An emotionally troubled young man from suburban New Jersey has moved to Santa Monica to be closer to his favorite film star. He also recently purchased a handgun, and he has been making openly paranoid statements to his landlord. The actress he believes he is in love with is flying out of LAX later this week—and he will do anything to be there to see her go.

Assassin’s Creed

It has been seven months since a graduate student in international relations dropped out of the University of Southern California after threatening a Jewish classmate for her public support of Israel. A member of the Israeli Knesset, well known for his hardline stance against an independent Palestinian state, is visiting Los Angeles next week. This former student will be waiting at baggage claim to greet him.