Three days I've been here running from one ministry to another, making phone calls, emailing the U. S. embassy, asking favors of friends and then favors of friends of friends. Nothing has worked. I want to be in Fallujah. But I can't get out of Baghdad. It's two in the afternoon on a Thursday in late October. I'm in a nearly empty shopping mall, at a Toll House cookie kiosk across the street from the Iraqi Ministry of the Interior. It's Fityan, Hawre, and me. We're waiting for a call from Fityan's cousin Tahrir, a captain in the police. He is inside the ministry negotiating my letter of permission into Fallujah.

In Fallujah there is a doorway I want to stand in. My friend Dan Malcom was shot and killed trying to cross its threshold twelve years ago. A sniper's bullet found its mark beneath his arm, just under the ribs.

In Fallujah there is a building I want to stand on top of. It was a candy store. The day after Dan was killed, my platoon fought a twelve-hour firefight from its rooftop. That was the worst day of the battle, the largest and bloodiest of the Iraq War. We began the morning with forty-six guys. By nightfall, twenty-five of us were on our feet.

That doorway in Fallujah, that rooftop—I remember exactly where they are.

Fityan's phone rings, startling him so much that a worm of ash tumbles from his cigarette. He brushes at the black T-shirt that is snug over his round belly. As he answers Tahrir's call, I try to decode the slushy tonality of Fityan's Arabic. His expression sags as he hears his cousin's report.

"They are asking for a $500 bribe," Fityan says. He tosses his phone onto the coffee table between us. Fityan and Tahrir are Sunni, with deep ties in Iraq's restive Al Anbar Province. I met Fityan through a friend of mine, an American who used to teach at a university in northern Iraq. He knew Fityan through one of his students, which is to say he hardly knew Fityan at all. Weeks ago, over long-distance Skype calls and emails, Fityan introduced me to Tahrir. The two of them promised that they could get me into Fallujah, and I've come a long way because of their promises. "If you were Iranian, it'd be easier," Fityan mutters. "The ministries are all Shia. They're giving you a hard time because you're an American."

Our server brings our drinks. Hawre, the photographer assigned to this story, sets down his camera and examines the enormous cup of coffee in front of him. "Fityan, tell him I ordered a medium." Hawre is an Iraqi Kurd from Kirkuk, north of Baghdad. His teeth are crooked and overlapping, like cards fanned out by an unskilled dealer. Whenever he parts his lips, he appears to be smiling. He is immensely proud that he barely speaks Arabic.

Fityan confirms that Hawre's coffee is the size he ordered.

"Toll House is an American chain," I say to Hawre, attempting to explain his enormous "medium." Everyone lights a cigarette.

It's been twelve years since I fought in Fallujah as a Marine. If a bribe is all that's preventing my return to the city—a place that's been in my thoughts every day since 2004—it seems I have no choice. "I could just pay the five hundred."

"They always do this bullshit," Fityan says.

They is Iraq's Shia-majority government, which has marginalized the country's Sunni minority since the U. S. officially withdrew in 2011. Shia flags emblazoned with the deific portrait of Ali—the Prophet Muhammad's martyred cousin and son-in-law—line nearly every government building, lamppost, and shopfront in Baghdad. Ali has an impenetrable beard, a confrontational stare, and a forest-green shroud covering his head. For the Shia, who believe that he was Muhammad's legitimate successor, he has become the personification of resistance to the Islamic State.

The Sunnis, meanwhile, who dominated Iraq under Saddam Hussein, claim that the rightful heir to Muhammad was Abu Bakr al-Siddiq, a companion of the Prophet's who was made caliph in a.d. 632. When the Islamic State established its modern caliphate in Mosul in June 2014, the group's leader, a slightly obscure religious scholar named Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim al-Badri, asserted a grandiose nom de guerre. Claiming his place in the succession, he declared himself to be Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

I slump in my chair and wait for Tahrir for another hour. I fought in Iraq for two years. I know that this country's dysfunction is millennia deep. Why did I expect that Tahrir and Fityan, two Sunnis from Al Anbar, would be able to navigate the bureaucracy of an Iranian-backed Shia government?

Then Tahrir appears, strutting past the cashier, who, like everyone else, is nearly a head shorter than him. "Elliot, bro, you look sad. Why the long faces?"

I'm about to ask if I should pay the bribe when he whips from behind his back a brown envelope closed with an official seal. Handwritten Arabic script is lashed along its front. I go to tear it open as if it were one of Willy Wonka's Golden Tickets. "Slow down," he says. He takes the envelope and places it on the table.

"What about the bribe?" I ask.

"I was fucking with you, habibi. You Americans think we Iraqis can't do anything right," he says. "I told you, the guy at the ministry is my friend."

We carefully remove the letter, a single page covered with seals, serial numbers, and many signatures. "What does it say?" I ask.

Fityan reads the text, his mouth silently forming the words in Arabic while the tip of his cigarette bounces over the syllables with metronomic precision. He glances up at me. "It says you're going back to Fallujah."

Early on Friday morning, the first day of the Muslim weekend, Baghdad is asleep as we drive out through the city's deserted streets. Fityan and Tahrir are up front, and Hawre's next to me in back, hungover with a pair of knockoff Gucci sunglasses pulled over his eyes. His head is against the window when his phone rings. The voice on the other end is frantic, and soon Hawre is frantic as well. He tucks his phone away. "That was my brother. At 4:00 a.m. the Daesh attacked Kirkuk."

Four days ago, the Iraqis began an offensive to retake Mosul from the Daesh, also known as the Islamic State. Thus far, an alliance of Iraqi security forces, Kurdish peshmerga, and Shia militias known as Hashd al-Shaabi, or Popular Mobilization Forces, has made steady advances toward Mosul, Iraq's second-most-populous city and the Islamic State's capital in the country. These gains come on the heels of more than a year's worth of successful offensives by Iraqi security forces in Tikrit, Hit, Ramadi, and Fallujah. Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi has staked the credibility of his government on the Mosul operation's success, appearing on television to announce the offensive in the black uniform of his elite counterterrorism forces.

The attack on Kirkuk was part of an Islamic State counteroffensive. We search for news about it on Facebook and Twitter. "The Daesh are fucking smart," Tahrir says, as we pull up to a checkpoint outside Baghdad. A sentry examines my passport and the Interior Ministry letter at length. Tahrir has worn his police uniform for good measure, an ad hoc mixture of camouflage pants and an olive-green safari shirt. His pistol is tucked into his waistband. Opposite us, the queue of vehicles entering Baghdad extends nearly half a mile. There is virtually no traffic departing for Al Anbar. We are waved through.

The highway stretches out with palm groves on either side. More than a decade ago, on daylong foot patrols, our platoon would rest in the trees' shade with our backs to their scaled trunks and our rifle barrels facing outward. Soon Abu Ghraib, the infamous Iraqi prison, appears. The cupolas of its guard towers menace the prisoners inside and the travelers on the road: Watch where you're going and what you do. Villages with low-slung dwellings and names as forgettable as passwords race by—Nasr Wa Salam, Zaidan, Amiriyat. There are also the places we named ourselves, because we knew no better, like the bulging peninsula cut by the Euphrates that separates Al Anbar and Babylon. We called it the Ball Sack.

After twelve years, everything is unchanged. And looming over it now, as it did then, is Fallujah. Fityan points up the road, where four- and five-story buildings form a barricade on the horizon. "There it is," he says. A picket of minarets stab heavenward, their sides paneled with crumbling mosaics. Everything anyone has ever built in this city is pocked with bullet holes. "Is it like you remembered it?" Fityan wants to know.

At a barbed-wire checkpoint decorated with flowers to welcome returning residents, we meet Colonel Mahmoud Jamal, the city's chief of police, who escorts us to his headquarters. He is a member of the Albu Issa tribe, which supported the Anbar Awakening, a Sunni movement that rebelled against Al Qaeda in Iraq, the Islamic State's precursor. We are served bread, fried eggs, and tea with a finger's worth of sugar lurking at the bottom. We sit in his office, with his unmade bed in the corner and a pair of his socks airing out on the windowsill. A clicking table fan circulates the inside air.

For nearly an hour, Colonel Jamal tells us how the city is being rebuilt, but what he says doesn't correspond with what we see. Though Iraqi security forces retook Fallujah from the Islamic State four months ago, in June, three quarters of the city's population has yet to return. There is still no electricity, no water, no sanitation. Colonel Jamal grew up here and has worked in and around the city as a police officer since 2005—longer than anyone, he tells us. "I will never give up on my home," he says. One can't begrudge him his persistence. In his job only an optimist—even a foolish one—could hold out any hope for success.

"The Daesh are vampires," Colonel Jamal says. "I insist on this description. They suck the life from everything." He suggests that we visit an Islamic State prison the Iraqi security forces discovered after liberating the city. I agree but also ask to visit a couple of other buildings, obscure ones. Before he has a chance to ask why, there is a commotion at the front of the police station. A tall officer in a well-starched uniform with deliriously embroidered epaulettes and a retinue in tow steps into Colonel Jamal's office. It is Brigadier General Mahmoud al-Filahi, commander of the Iraqi army's 10th Division, which is responsible for all of Al Anbar Province, here for an impromptu visit.

Colonel Jamal assigns us an escort of two soldiers and ushers us hastily out of his office so that he can speak with the general alone. As I pack up my things, Colonel Jamal explains our plans to General al-Filahi. The general's questions are pointed. "And what is it that you're looking for?" I hesitate, not certain that I want to offer up this detail. Before I can respond, the general adds, "Perhaps you are looking for your WMDs?"

I smile and laugh lightly at his joke. He does not.

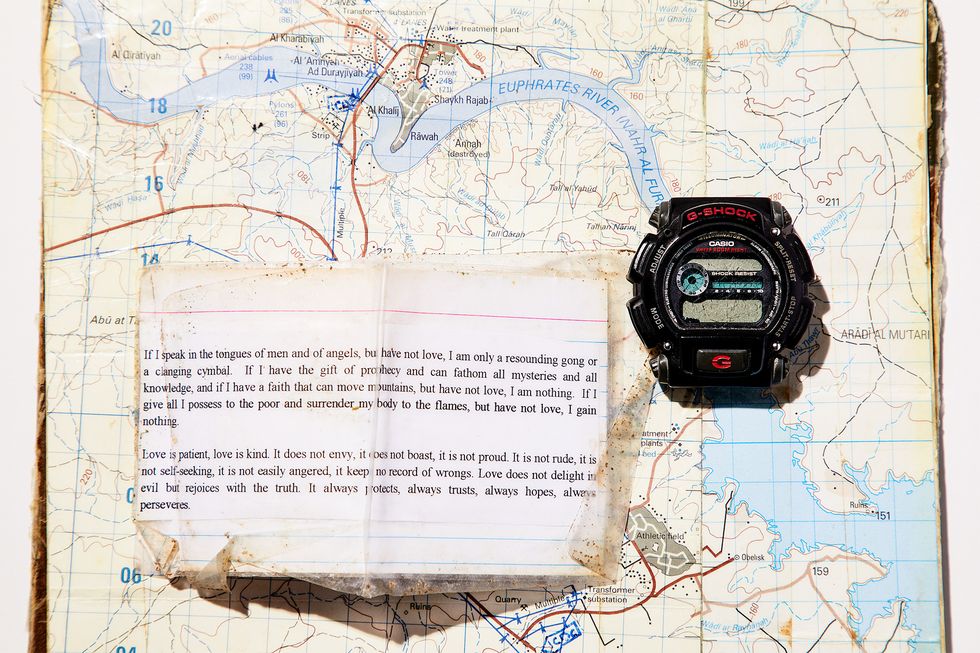

Dan was a great chess player. We played our last game sitting across from each other, with his magnetic set spread across an upturned crate of Meals Ready to Eat. "Life is like chess," Dan would sometimes say, usually when he was winning.

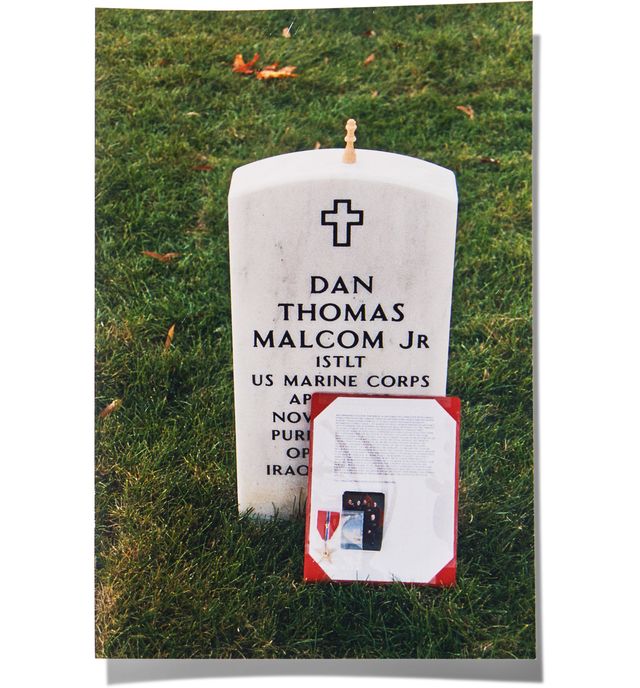

The door he was trying to get through when he died was on the rooftop of a five-story building in the Fallujah mayor's complex. We called it the High Rise. My platoon was spread on top of two identical buildings next door, which we'd dubbed Mary-Kate and Ashley, after the Olsen twins. It was November 10, 2004, during the opening days of the battle. Dan had run up to the roof after friendly artillery nearly fell on my platoon. The shells were so close I could hear the steel fragments slapping against the side of Mary-Kate, where I was lying prone on the roof. All of us had our mouths open to keep the blast overpressure from rupturing our eardrums. Dan crawled across the top of the High Rise and managed to call back to our headquarters. He got the artillery shifted away from us, and I picked up the radio to thank him. That's when I heard my company commander call for a corpsman. Dan's body had collapsed across the threshold when he was shot, and he'd died almost instantly. He's buried at Arlington now. I heard that his magnetic chessboard was in his cargo pocket when he was killed.

After we leave the police headquarters in Fallujah, Hawre wants to walk. So do I. But our two escorts shepherd us into the bed of a pickup truck instead. The mayor's complex is a few hundred meters away, on the north side of Highway 10, whose four lanes bisect the city. Across the street is the timeworn candy store, the other place I want to see. Tahrir begins to argue with our escorts in Arabic, insisting that they take us there. Fityan pulls me aside and says, "We're not telling them that you fought here, so they're a bit confused." I can't disagree with his judgment. Visiting this city as a former Marine feels like walking through New Orleans if your name is Hurricane Katrina.

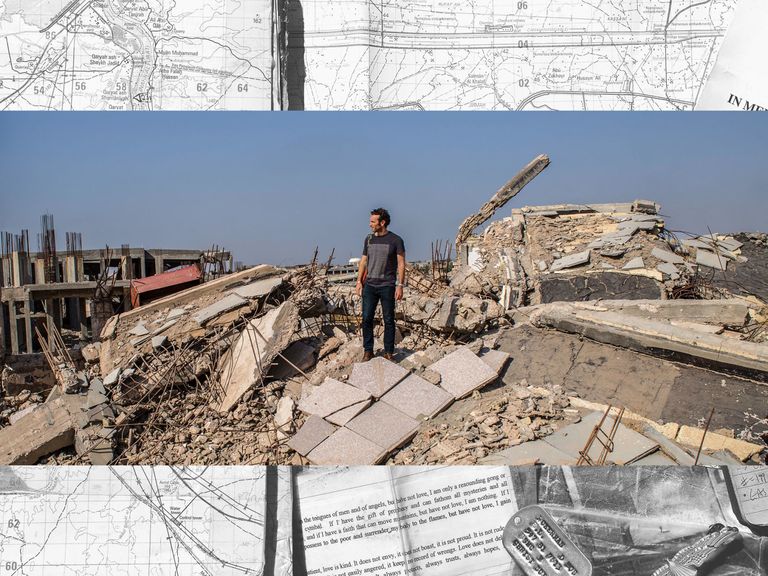

The escorts drive us to what is left of the mayor's complex. The Islamic State leveled most government buildings during its occupation. Our escorts warn us to be careful as we step through the rubble. The city has yet to be demined, and booby traps are uncovered daily. Among fragments of cement, I stumble across a human hipbone. I also find the skeletal remains of Mary-Kate, from whose rooftop I had called Dan. Searching the horizon, I see only blue sky where the High Rise once loomed. Mysteriously, not even the wreckage remains.

Tahrir glances at the rubble and asks, "Is this where it was?"

I point at the empty patch of ground. "No, it was over there."

"The door, habibi?"

"I guess it's gone."

I find the candy store, where insurgents surrounded my platoon the day after Dan was killed. Earlier that morning, at three o'clock, we had crossed Highway 10 in advance of a larger assault of nearly one thousand Marines that was scheduled for a few hours later. I had never seen the outside of the candy store in daylight. "This is the place," I tell Hawre. He begins to shoot photos, which only increases the suspicions of our Iraqi escorts. They glance in my direction and whisper among themselves. A sign on the side of the structure is in English. It reads, MOONLIGHT SUPERMARKET.

A rusted mesh fence, padlocked shut, encircles the building. I climb up the side. By the time I am on the rooftop, I am covered in a familiar dust. I recognize not so much the building as the vantages it offers. The view from where we set in our medium machine guns so they could rake a long street. The approach where we waited desperately for an armored ambulance as one of the Marines, who'd been shot through the femoral artery, was bleeding to death. The southeastern corner where I crouched alongside my platoon sergeant, who in his early thirties seemed infinitely old and wise, seconds before he was shot in the head, only to miraculously survive.

I try to imagine this place not as a battlefield but as a community of homes and businesses. Many of our most iconic cities—Rome, Istanbul, Athens—have a layered architectural aesthetic, each population having built on what its predecessors created. Fallujah is different. It is defined not by creation but by destruction.

My eyes cast out, searching for hard-fought neighborhoods and alleyways, for unrepaired scars on the buildings. I am looking for the marks we left behind. I see them everywhere, commingled with the marks left by others. They have become the city, both battlefield and home.

Colonel Jamal is eager for us to see the torture house. We've driven into Fallujah's Jolan District, where townspeople strung up the burned bodies of four American Blackwater contractors from a bridge in 2004, beginning the first battle for the city. The prickly scent of cordite lingers on every street in Fallujah, but it is heaviest up here. We follow Colonel Jamal into the courtyard of a mansion. In the foyer, light pours through stained-glass windows. Above us a chandelier's crystal pendants tinkle in time with a soldier's footfalls in an upper bedroom. We enter an atrium. A winding staircase ascends beneath a domed roof painted purple, yellow, and pink. A human femur rests on the tiled floor.

"These were the mass holding cells," says Colonel Jamal, "and the offices for the Daesh courts." Hastily welded steel doors enclose salon-sized rooms with bags of dates and almonds stashed in the corners. "This is all they fed the prisoners," he explains. On a single shelf rests a small library of religious texts, with two curious exceptions: a collection of letters by Nelson Mandela with a foreword by Barack Obama, and The Short Stories of H. G. Wells.

Colonel Jamal says it's time for us to go next door. Instead of walking outside, he crawls through a hole that Islamic State fighters sledgehammered into the wall so they could move between buildings without being detected by coalition aircraft. "This is the place they don't want you to see," Colonel Jamal says of this second house. A fire has ripped through the interior: Heat has warped and melted air-conditioning units, glass, anything not made of stone or steel. An eerie silence possesses every room. Hardly anyone in our group speaks, and none of us hazards more than a whisper. There is only the rhythmic sound of our steps crunching against the charred wreckage—that and the smell, a cauterized scent sickly sweet with the undertones of death.

We climb a stairwell. A hand-cranked winch is fastened to the banister. A pulley is bolted to the ceiling. The steel wires hanging from it have loops just large enough to cuff a pair of human wrists. Car batteries are stacked in a corner, and next to them are bales of copper wire with the insulation stripped away, as well as a melted plastic chair. It seems gratuitous to ask what it's all for. On the second floor, the windows are covered. It is pitch black. I turn on my iPhone's flashlight. Six steel cages are arrayed in two rows. Each cell has a thin mat and a pillow, and a padlock is notched jauntily onto every door. "Step inside," Colonel Jamal insists. I hesitate. He asks again, challenging me. I duck my head and walk into the solitary-confinement cell. "Turn off your light," he says. I do, for maybe three seconds, possibly for as long as five—long enough, in any event, for him to tell me through the impenetrable darkness, "What you see are the accomplishments of the U. S. government."

Spray-painted in white on an interior courtyard wall is the first part of the Shahada: lā 'ilāha 'illā-llāh, "There is no god but God." A handful of hair dryers and curling irons are heaped beneath the Islamic State graffiti. Colonel Jamal dips his wrist effeminately and laughs. "The Daesh," he says, "are very vain, especially about their hair." He is still amused by this when we amble into the street and squint against the sunlight.

As we walk, the city's energy refreshes Colonel Jamal. He is eager for us to speak with the locals. Sitting in front of a boarded- up shop is a stout man in a gray ankle- length dishdasha and Nike sandals. He is passing a tangle of wire to his nephews to coil around a scrap of wood. "Wire is expensive, so we're digging up what's left in the city and using it in our homes," he explains.

The man's name is Ahmed Abas al-Jabor. He is a mukhtar, a community leader. When I ask if he was here during the Islamic State's occupation, he insists he was not. His nephews shift restlessly and insist that they, too, left the city. Fityan, who has been translating, leans toward me and whispers, "No one is going to admit that they stayed." Al-Jabor continues, "Many are waiting to see if the insurgents will retake the city."

Colonel Jamal cuts him off. "Don't call them insurgents."

Al-Jabor stares back blankly.

"You must call them Daesh."

Every tenth house or so, someone is trying to rebuild, clearing out a courtyard, sweeping up debris, tampering with a generator. True to Fityan's word, citizens across the board tell me they left Fallujah during the Islamic State occupation. We see a smattering of Iraqi police and army checkpoints. Many fly the Shia flags emblazoned with the image of Ali that were so ubiquitous around Baghdad. The evidence of this summer's battle—and those that preceded it—is apparent everywhere.

We spend the afternoon outside Fallujah, at Habbaniyah air base. Unbeknownst to us, Colonel Jamal has arranged a VIP visit to the Iraqi police's Special Tactical Regiment. The regiment's commander, Lieutenant Colonel Adel Hamed, tells us hair-raising stories about the recent battles for Ramadi and Fallujah, replete with slick promo videos made by his in-house media team. His men, trained by Navy SEALs, served as shock troops in both battles. When I ask the colonel how his background landed him a job as the leader of an elite commando unit—he once worked as an administrative officer—he shrugs and says that nobody else wanted the position. He tells us that he raised the Iraqi flag over Ramadi's city hall himself and then shows us a video to prove it. (At his urging, we watch it several times.) He is also eager to show off a picture of himself with a bandage over his left eye, sunglasses down. The photo shows him in Ramadi, strutting along a highway flanked by the skeletal wreckage of buildings, his men trailing behind him. Gesturing upward, presumably at the enemy, his hand is formed into a karate chop. "I took a grenade fragment in my eye," he says. "It's still there. And on that day, I realized my purpose in life: I love fighting more than anything else."

After a tour of his barracks, armory, and motor pool—the last of which is filled with bullet-riddled Humvees and the occasional ballistic windshield shattered by rifle fire—I find myself chatting with one of his troopers, a slim but debonair man with a sunken chest and tobacco-stained teeth. He speaks perfect English and is the regiment's joint tactical air controller, meaning he is qualified to call in airstrikes from Western warplanes. He calls himself Maximus, a nod to Russell Crowe's character in Gladiator. It seems the SEALs' talent for self-promotion has rubbed off on their Iraqi counterparts. Maximus, one of the most well-trained troopers in this unit, is also his regiment's press liaison. He follows us around wearing a khaki safari vest with media officer embroidered on the chest.

"I used to work with the Marines," he says. "Three-seven, one-nine, two-eight—those are my boys." I tell him I was with one-eight, otherwise known as the 1st Battalion of the 8th Marine Regiment. "Right on, man," he says, his head nodding in a rhythmic groove. We chat about Fallujah, Ramadi, and our respective battles in these cities. When I offer my hand, he shakes it before rotating his palm and pulling me in for an American bro hug.

Soon we are back on the road, driving toward Fallujah. "What did you think?" Tahrir asks. Before I can answer, he continues, "They're as good as most Americans."

I can't disagree, but the conclusion is unsettling. With select units like the Special Tactical Regiment, the United States has managed to create a security apparatus built in its own image. These elite groups are well trained and well equipped and have won decisive battles against the Islamic State in Fallujah and Ramadi. They will likely do the same in Mosul. But winning battles was never the U. S. military's problem. The problem was always what came after, the rebuilding.

As the sun descends, the rubbled outskirts of Fallujah come into view. We pull over by Moonlight Supermarket so that Hawre can take a few more photographs before we return to Baghdad. Hawre wanders across the street, followed by Tahrir, who is soon surrounded by residents. His uniform seems to confuse them. I imagine they have mistaken him for a member of the local police and are accosting him with questions about when, if ever, basic services will return to their city.

While Fityan speaks to our Iraqi escort, I notice a broken cinder-block wall on the back side of the supermarket. It forms a corner, maybe three feet on one side and five on the other, and rises a little higher than my knees. I crouch behind it, into a familiar position. When our platoon escaped from the candy store twelve years ago, I found myself pinned behind this tiny wall for about twenty minutes as we struggled to advance deeper into Fallujah. A flood of memories returns. The clattering of tank treads. The panicked squelch of radio traffic. The terrified, uncomprehending looks of the Marines around me. How by that afternoon I had shouted myself hoarse and was reduced to issuing orders under fire in a depleted whisper. I glance over the wall, toward the mayor's complex, to the void in the sky where the High Rise once stood, the place where Dan was killed. I reach over to the wall's far side. Under my hand, I can feel tiny gouges. My fingertips read them like braille. I wonder if they were made that day in 2004.

I occasionally still play chess. During a game with a Turkish friend at a café in Istanbul, I once reiterated Dan's words, explaining as I took a piece that life was like chess. My friend laughed at me. "No, it's not." He gestured toward another table where players rolled dice from a cup across a board. "Life is backgammon. The game takes skill, but it also takes luck." As he said this, I thought about the bullet that found Dan. I often think about the bullet that never found me.

When I return to Fityan and our Iraqi escort by the car, they are silent for a moment until the soldier asks what I was looking at.

I tell him that I've been here before. Then I explain about the candy store and the mayor's complex. He wants to know why I came back.

"To see what it was like now, I guess."

He looks at me, perplexed. "It is just as you left it."

Two days later, Hawre and I are driving again. Fixed along the horizon is Bartella, on the outskirts of Mosul. The town is burning. Noxious columns of smoke lift upward, like stitches fastening earth to sky. Yesterday Hawre and I left Baghdad and headed north to join the offensive. Now, around 2:00 p.m., our Toyota HiLux is stopped on the shoulder of the road, alongside a mélange of tanks, armored bulldozers, and black Humvees from the Iraqi Counter Terrorism Service's 1st Brigade, also known as the Golden Division. Bartella is a Christian town and the Golden Division, with its Shia flags fluttering from the back of every other vehicle, will soon liberate it from more than two years of Islamic State occupation.

Soldiers in black uniforms and black ski masks escort a pair of priests into a white Suburban, and I find myself trying to remember when, in the history of war, the good guys wore black. The priests plan to hold Mass that afternoon in the Mart Shmoni church, in the center of Bartella. As their Suburban pulls into the street, Hawre and I pull up behind them. A soldier with the Golden Division cuts us off. I offer my press credentials—a dog-eared letter from this magazine—and my passport. Hawre argues with him in Kurdish. He hands the soldier his Iraqi identification card. "He wants to keep your passport until we come out of Bartella," Hawre says.

"I'm not giving him my passport."

"Then we can't go," Hawre says. A beat passes. "Don't worry," he pleads. "I've got his cell-phone number."

The soldier grins. He's missing one of his incisors and another tooth is made of gold. "I be here when you back," he tells me in choppy English. I hand him my passport and our HiLux slides behind the priests.

A day after the Golden Division launched its assault on Bartella, we hear early estimates that eighty Islamic State fighters lie dead in the town. On either side of the road, scorched swaths of dry grass spot the ground. Nearly every building is a mass of twisted rebar and collapsed cinder blocks. Snaps of rifle fire and the low percussive thuds of artillery and airstrikes can be heard in the distance, causing confused flocks of birds to leap from their perches and juke across the skyline. A sedan passes us going the opposite direction. Hunched behind its steering wheel with his eyes barely above the dashboard is a boy not much more than ten years old. Two little girls even younger than him are in the backseat. They are wearing school uniforms. We pass a road sign: MOSUL, 27KM.

Unlike Fallujah, which is sixteen square kilometers, Mosul and its environs are sprawling. The battles for Fallujah in 2004 involved little maneuver. We cleared house-to-house through dense urban blocks. This battle, by contrast, has seen movement along multiple axes of advance. We are to the east of Mosul, with the Iraqi security forces. To the north and south is the Kurdish peshmerga, as well as other units of the Iraqi security forces. Waiting in reserve is the Iranian-backed Hashd al-Shaabi, whose presence is controversial. Prime Minister Abadi has promised that only Iraq's nominally secular security forces, including the Golden Division, will participate in the final fight for Mosul itself. But if the Islamic State proves too much for the Iraqi security forces, the peshmerga and Hashd al-Shaabi may find themselves immersed in the battle, further inflaming sectarian tensions. What will happen inside Mosul is the question on everyone's mind.

A sergeant flags us down, instructing us to park. Hawre and I will have to travel the rest of the way on foot. Humvees and dismounted soldiers rush past us, setting up their positions in the newly liberated town. The soldiers' voices are jubilant. Several who fought this morning now strip to the waist and wash with bottled water. Others clean weapons. I meet a soldier who is working on the grenade launcher in his Humvee's turret with a rag and oil, and ask him for directions to the church. He isn't certain, but he is eager to talk. He says that the Daesh "are good with ambushes and IEDs, but not as good in conventional battle." He explains that his family is proud of him: "I have been fighting nonstop for a year, but they don't worry. If I die, I will be a martyr." He insists that I take down his name: "Maher Rashid from Baghdad." I ask him again if he knows where the church is. Before he can answer, the bells toll, for the first time in two years. "That way," he says.

Affixed to the dome on the Mart Shmoni church are two tree limbs hastily lashed together into a cross. An Iraqi flag flies from its top. There is an enormous gouge in the side of the church in the shape of a crucifix, no doubt the work of the Islamic State. Inside, upturned pews litter the nave. The altar in the sanctuary is covered in rubble but still intact. The priests continue to toll the bells. Soldiers file in and out of the ravaged church. They take selfies next to destroyed artifacts. Not even the priests think to stop them.

Between here and Mosul, there are a dozen more Bartellas to clear. The noose is tightening on the Islamic State, but gradually. Four months from now, in February, Iraqi security forces will control only the eastern half of the city. But today, the Golden Division's work is done. The discipline it maintained for the battle ebbs away, devolving into horseplay. The soldiers take off their boots and body armor and walk around in flip-flops and T-shirts. A grinning artillery gunner wears a T-shirt with a skull that reads: KILL 'EM ALL LET GOD SORT 'EM OUT! Another soldier has chosen a tank top with an airbrushed portrait of a lion staring into the sunset. A burly sergeant is attempting to throw his bayonet as close as possible to his opponent's foot, in a makeshift game of mumblety-peg.

I feel a tap on my shoulder. A soldier stands behind me, cradling a ceramic statue of the Virgin Mary. I take his picture, which seems to satisfy him. Then a lanky, baby-faced private wanders up and pantomimes slashing the blade of his bayonet across his own neck. His eyes go wide, and with a broad, homicidal grin he says, "Daaaeeeeesh." His buddies laugh. The sergeant wanders over. He explains that tomorrow they'll continue their advance at first light. They plan to liberate three more villages, he says, before muttering under his breath, "Inshallah."

I am anxious to retrieve my passport, so I find Hawre. We walk back toward our HiLux. Ahead of us is a consistent rumble of artillery and airstrikes. Behind us we can hear the chatter of the Golden Division as it beds down for the night. The soldiers' voices are cheerful, certain of victory. And they probably will take Mosul. But even if the Islamic State loses all of the cities it occupies across Iraq, the group will likely plague the country with a Sunni insurgency that will cause further sectarian violence, a repeat of the past decade. I think of all the cities we took in our war: Fallujah, Ramadi, Najaf, Nasiriyah. Winning those battles did little to end the fighting. What difference will Mosul make?

Someone calls out from behind a flatbed ammunition truck parked in a field. When I turn, a hulking figure in an old American- style desert uniform with a brown T-shirt jogs toward me with a broad smile, his enormous gut swaying in rhythm with his steps. "Cigarette, habibi?" I offer him a Marlboro Light. "Oh, no, I don't like Lights. You American?" he asks, taking out one of his own cigarettes, a brand called Pine. "My sister, she lives in America, in Texas."

"Oh, yeah, where in Texas?" My mother is from Texas.

He looks confused. "In Texas!"

"No, what part—Dallas, Houston?"

"Like I say, in Texas."

His name, he says, is Firaz Saleh Mohammad. I take it down at first just to be polite. He is a sergeant. Then he explains how he helped his sister immigrate because "I've been a soldier longer than anyone. I was ICDC, habibi," he says, referring to the Iraqi Civil Defense Corps, the precursor to the Iraqi army. It was founded in 2003 and summarily dissolved a year later. "I have been here since the very beginning, starting with the ICDC and Marines in Fallujah in 2004. No one has seen as much as I have seen."

I tell him that I was in Fallujah in 2004.

"I was with one-five. You know one-five?"

"Yes, I know one-five." A few friends come to mind. "I was with one-eight."

He puts his arm around me and laughs. "What are you doing here?" he asks. "Did you get lost?" I don't say anything, and he doesn't push it. He just smiles, jabs his finger in my face, and says, "My sister, she is very happy in Texas." As he finishes his cigarette, he's looking to the west, toward Mosul.

"What do you think's going to happen?" I ask him.

He shakes his head. "This? The future of all this, it cannot be predicted."