One September afternoon in 1968, Rowland Bowen, a renowned cricket historian and establishment-baiting controversialist, walked into the bathroom of his house in Willingdon Road, Eastbourne, set out a hacksaw, a hammer and a chisel, and sat down in the bathtub. Following instructions gleaned from years of obsessive amateur study, he then set about methodically amputating his own right leg.

Why he did it, nobody was quite sure. Bowen was many remarkable things but he was definitely not a doctor. Neither was there anything wrong with his leg. Years earlier Bowen had lost a finger too. He explained that one away to his remaining friends as an accident; he’d just been careless while chopping up food for the giant hounds that surrounded him as he sat at his typewriter. The term Apotemnophilia – a neurological disorder characterised by an intense and long-standing desire for amputation of a specific limb – was not commonly encountered until a decade later.

Bowen was 52 years old when he chopped off his own leg. When he finished the gruesome procedure, he simply limped his way to the telephone, leaving behind a trail of blood, and called himself an ambulance. The bizarre story was carried in newspapers around the world. “A major who carried out a do-it-yourself amputation on his own right leg to prove it could be done painlessly today was recovering in hospital,” said London’s Sun.

“At Eastbourne Hospital (Sussex) surgeons in an emergency operation ‘tidied up’ the limb, which had been cut off below the knee. A doctor said: ‘The major seems to be realizing the foolishness of his action.’ The Major was known to have a keen interest in amputation. Major Bowen, who works for the Ministry of Defence, is a cricket historian.”

Added Sydney’s Daily Mirror: “He is Major Rowland Bowen, 52, a life member of the MCC, who runs a magazine called Cricket Quarterly, and writes on the game for several newspapers.”

The doctor was right in all senses bar his patient’s moment of realisation. In truth, Bowen didn’t see the episode as foolish at all, and he couldn’t quite comprehend all the fuss generated by his foray into self-administered surgery.

On 25 September he wrote to the Brisbane lawyer and cricket bibliophile Pat Mullins, in correspondence that now resides with Mullins’ book collection at the Melbourne Cricket Club library: “I am sorry all my friends should have been fed this piece of scare news about me,” Bowen wrote. “How the press get hold of such things I do not know, and why it would have been regarded as anything of importance to anyone else I do not know.”

Swiftly, and without further mention of his former limb, Bowen moved straight on to what he considered a far more pressing matter: was England paceman Fred Truman chucking the odd delivery?

‘A fundamental ignoramus’

One of three sons of a London solicitor, Rowland Bowen was born on 27 February, 1916 and educated at Westminster, an upbringing he would later describe as “conventional English upper middle class”.

After school he joined a firm of merchants but found the “immorality” of commerce disagreeable, so either side of WWII he served in the Indian Police and Indian Army. The war office promoted Bowen to the rank of Maj in 1958, and upon his return to Britain he settled into a day job at the somewhat obscure Joint Intelligence Bureau, gathering topographic, economic, scientific and atomic intelligence.

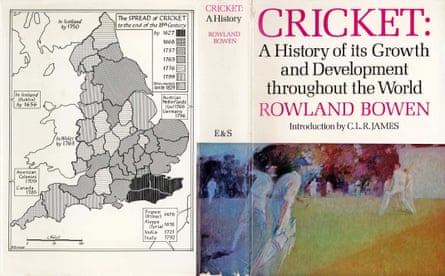

In time though, Bowen would become better known throughout the world for his arch, revolutionary writings on cricket – first in his trenchant and wilfully esoteric journal, The Cricket Quarterly (1963-71), then in his book-length magnum opus, Cricket: a history of its growth and development throughout the world. The latter, a culmination of a decade’s furious labour, elevated the curmudgeonly Bowen into the company of H.S. Altham among the game’s most significant historians, and drew breathless praise from C.L.R. James.

Yet around Rowland Bowen – “The Major”, they called him – there was always an air of mystery and suspicion. Was he completely mad? Could you really trust the word of a man who chopped off his own limbs out of curiosity? Was he a spy? Decades worth of Bowen’s letters to friends and associates gave rise to the latter theory. “My ‘real life’ work is in Intelligence,” he once wrote to Mullins. “Both jobs make the protection of sources paramount”.

The cricket writer Murray Hedgcock – who in the space of the last three decades has gathered seven file boxes of material on Bowen with a view to writing an overdue biography – says his research has uncovered plenty of evidence to suggest Bowen was not in fact James Bond in a tweed jacket, but he could also never rule it out. For one thing, Bowen claimed to have played a central role in the Cuban Missile Crisis, being the photographic interpreter responsible for identifying the ballistic missiles on board Russian cargo trawlers. Sure, why not?

“I have found a couple of fresh contacts with useful information, both personally and on his career, but his precise Intelligence activity remains clouded in mystery,” Hedgcock told me. “There is much talk that he was with MI5, but that is not an organisation which makes public a staff list.”

It was in the late 1950s that Bowen first announced himself in the world of cricket letters by exposing prominent historian Roy Webber’s slipshod work establishing a list of early County championship winners (the title was not properly codified until 1890). It was an episode that left Wisden editor Norman Preston exposed to ridicule when a TV quiz show contestant claimed, as per Webber’s figures, that Sussex had won the title in 1875.

That was the beginning of an ongoing feud between Bowen and Webber, a kind of cricket history wars played out in the pages of Wisden, The Cricketer (where Bowen wrote a column called “At the sign of the wicket” until an inevitable falling out with his editors) and Playfair Cricket Monthly. “I wanted to sink him without trace,” Bowen would later write of Webber in a letter to his Cricket Quarterly confrere and fellow historian Peter Wynne-Thomas.

In another letter to Mullins, Bowen explained that the genesis of his idiosyncratic publishing career was the fallout from his many slanging matches, a prickliness that quickly reduced the number of outlets for his writing: “Neither Playfair nor Cricketer would touch me of course,” he wrote. “It was because [E.W.] Swanton, who doesn’t like me (feeling is reciprocated firmly) got control of The Cricketer that Cricket Quarterly was ever started. Playfair don’t like me because I exposed Webber for the fundamental ignoramus he was.”

After Webber’s untimely death in 1962, Bowen quickly found himself a new cast of fundamental ignoramuses and the die was set. For all his brilliance, he was a character destined to put noses out of joint, and saw all around him only charlatans and know-nothings. Thankfully for future generations of scholars, it was this frustration at the quality of what was available to read that provided the impetus for his own remarkable body of work.

“My first impulse to writing anything about the game was solely to correct error,” Bowen wrote in his book’s introduction. “That led me on, and on. In ten years or so of research and writing I have been astonished at the way long-accepted facts have proved on investigation to have been no facts at all, and much-cherished opinion quite legendary. In establishing many fresh new facts, I hope I have not also laid the foundation for other myths.”

‘One of the best read of cricket students’

The gobsmacked initial reaction to Cricket: A History, and its ongoing, if little acknowledged, influence on the way cricket is written about and discussed now should be more than mere footnotes in the game’s lore, because every cricket historian since stands on Rowland Bowen’s shoulders.

Cricket writer and historian Gideon Haigh bought his copy at a secondhand book stall at Hove. “No sooner had I taken possession than a seagull dropped a huge crap on the cover,” he says. “I took this as a good omen.” Almost 30 years on from his first read, Haigh says Bowen’s masterwork is “just about the only synoptic history of cricket that matters... I consult it more or less constantly.” Peter Oborne would later label it cricket’s “unrivalled history”.

At the very least it stirred the pot. Bucolic Hambledon’s status as the so-called cradle of the game? “One does not put a lusty young man into a cradle,” Bowen sniped, and his forecast for the game’s future made for awkward reading. The appendices, running to 148 pages (a third of the book) were themselves a work of minor genius, freeing the main text from an overload of statistics and factoids, and providing a revelatory chronology of the game since the 13th century. To the dismay of his contemporaries, ground zero for Bowen was France, and the first mentions of “crosser”, the French verb meaning to play “crosse” and a catch-all term covering any game played with a clubbed staff and ball, including golf, hockey and cricket.

It also didn’t shy from lashing the game’s administrators, and pondering cricket’s future viability while such conservative forces ruled the roost. “Bowen argued that cricket waxed with industrial and imperial England and that it was waning as they too declined,” Martin Kettel wrote in 1993, “He believed it was riddled with racism and that most of the agonies of the sport centred on the wishes of those who run the game in England to preserve something which was doomed. Put like that it sounds like a socialist workers party pamphlet, and in a way it read like one too, only this one was right.”

Though their accounts of the game’s history varied markedly, Altham – who used as the basis of his own 1926 magnum opus a series of articles written for The Cricketer – was one of Bowen’s key inspirations; for the best part of a decade Bowen tested his research in essays for the same magazine, then the more scholarly Cricket Quarterly.

Where Altham had dealt primarily with the game’s rise as an international contest (“similar to those histories of England which tell a great deal about the kings and queens, much about the barons, something about parliament but hardly anything of England itself,” was Bowen’s appraisal), Cricket: a history, concerned itself with grander themes. “It is my purpose,” Bowen wrote, “ to try and tell the full history of the game, and without confining the study to one class, or one section, or indeed one country.”

America’s contribution to the game until the end of the golden era was restored, Bowen adding that John Barton “Bart” King could credibly be labeled the game’s greatest ever fast bowler, and the full global sprawl of cricket’s history was laid out in the one book for the first time ever. In a sense, Bowen was the original associate cricket hipster, though it’s doubtful he would have put it in those terms.

Guardian cricket correspondent John Arlott’s Wisden review is, with hindsight, revealing in both content and context; 1970 was, in Arlott’s view, among the top three years for cricket literature in the post-war period, and it was Bowen’s text with which he led his summary of the 76 books put forward for review that season.

“Cricket: A history of its growth and development throughout the world by Rowland Bowen is unique in my experience as a major work on cricket written from a wide view, in disapproval of the game’s establishment, and in expectation of the imminent demise of the first-class game,” Arlott wrote, deeming Bowen “one of the best read of cricket students.”

Arlott was, in fact, Bowen’s most prolific booster, writing about the book at greater length still in the Guardian – a more hospitable home for The Major’s worldview than rival papers, to whom he was a relentless contributor of letters to the editor. “The immediate impact of the book will be to set many traditionalists by the ears,” Arlott wrote (under the headline: “One man’s critical view of cricket”). “But in the long term it should open minds on many aspects of the game’s past and present.”

“Major Bowen has probably read as widely as anyone on the subject of cricket; he has followed that study by detailed inquiry and has woven his mass of information into his own theories... [He] will be greeted with at least as much indignation as agreement; but even those who most strongly disagree with him will find his book compulsive reading.”

Among other reactions, endorsements didn’t come any more highbrow than that from cricket’s marxist philosopher in residence, C.L.R. James, author of the canonical Beyond a Boundary. “This is the type of history which I have never read before,” James beamed in the book’s introduction, “and whose forebears, either in method or material, as far as I know do not exist. Let me add that I do not expect, within the next generation, to see any book of its kind or quality again.”

Alas, it was also Bowen’s only book. Published by Eyre and Spottiswoode to reactions ranging in tone from from staggered appreciation to utter bemusement, it was never reprinted.

‘Ideally, I am an anarchist’

Perhaps it is not strange the world quickly forgot even a writer as brilliant as Rowland Bowen. Cricket history is hardly a sexy topic in the game’s current milieu, and even when he was alive, Bowen never made an influential friend he couldn’t turn into an avowed adversary.

“It is a great mistake to prattle about the value of cricket,” Bowen once said. “It has suffered much and will continue to suffer at attempts to identify it with early Victorian middle class morality and outmoded public schools ideals derived from Dr Arnold of Rugby.”

As he delved further into the namby-pamby explanations offered by his forebears and questioned everything the game stood for, it is not hard to imagine the speed at which Bowen’s list of enemies grew. He huffily resigned his MCC membership in reaction to, among other perceived blights on its own image, the club’s failure to condemn apartheid. Anyone who disagreed with Bowen on that topic was a “racialist” or a “typical Tory”. An articulate polymath and a product of privilege, he developed an insatiable desire to see every element of Britain’s establishment smashed to smithereens.

Interviewing Bowen in the late 1960s for an obscure, self-published biography, Australian cricket society founder Andrew Joseph encountered a man of jarring philosophical contradictions: “Given the background outlined above one should have the ultra conservative British establishment yes-man, the very stuff of the Empire, admirable in many respects, but – rightly or wrongly – somewhat obsolete in this day and age,” Joseph wrote.

“Ideally, I am an anarchist,” said Bowen, putting him straight. “By which I mean that in a suitably intelligent society anarchy in its real sense would be, to use the accepted form of government. I do not believe that the traditional institutions of society are worth maintaining or preserving once they themselves have lost any useful living content to which an intelligent person can give his assent.”

“I believe this applies to much of the greater part of British political life and institutions at the present time. We live in a fast-changing society and much to which willing assent could have been given twenty years ago is now an empty sham.”

As he continued with his Bowen profile, Joseph started receiving warnings from friends at the Melbourne Cricket Club. “Highly intelligent man that, but, uh, if I were you I would not, uh, mention his name too often at Lord’s,” an old stager told him. “People either admired the man tremendously or disliked him with a ferocious intensity.”

Bowen couldn’t help adding a provocative dig at Marylebone, telling Joseph: “There is even a good case for nationalising Lord’s.”

The man with the poison pen

To read back through issues of The Cricket Quarterly, where it all started for Bowen, is to marvel at the ambition and resourcefulness of a single man, but also, to appreciate the fear that must have filled the hearts of authors whose books came under his discriminating gaze. In CQ’s reviews section, Bowen took deadly seriously his role as reader advocate, lashing writers and publishers alike when the product wasn’t worth its cover price.

“Bruce Harris produced a third-rate English journalist’s description of third-rate Australian journalist’s attitudes to Jardine,” went one disdainful summary. Bowen delighted in questioning the cult of Neville Cardus, and had a particular distaste for journalese: “It is a strange thing, is it not, that a man past eighty should now spend six pages glorying in hoodwinking his newspaper and his readers by having written an account of a match at which he was not present? This is the sort of thing that is often done in Australia.”

Assessing A.A. Thomson’s Cricketers Of My Times, Bowen became enraged by the author’s idiosyncratic acronyms, like O.B.L (“ordeal by Laker”): “It degrades his work from that which could have had a lasting place in cricket literature to the same sort of level as novels read by house-parlour-maids.” Of another Thomson effort he complained: “This is not book writing, it’s book manufacturing.”

In the least surprising development of the magazine’s short, volatile history, publishers eventually stopped sending him their books. At that point Bowen simply doubled down; now readers really were getting an unflinchingly honest appraisal of each book’s monetary value proposition, because he was paying for them all himself. Cue this take on Ronald Mason’s Sing All The Green Willow: “We can only consign it to that sadly growing pile of rubbish which the cricket publishers have been so bent on increasing.”

‘The whole corpus’

Whoever finally gets close to the full truth about Rowland Bowen the man will have done exceptional legwork, as befits a historian of such indefatigable spirit. His combustible nature and fractious dealings with his contemporaries were probably best summed up by the prolific historian and Bradman biographer Irving Rosenwater in a 1994 letter to Hedgcock.

“I have written 10,000 words on him which have lain idle – deliberately idle, for it would be damaging for any writer to publish an appraisal (let alone an honest appraisal) of the man,” wrote Rosenwater, adding that if anyone saw “the whole corpus of the Bowen story, one would at once, out of decent necessity, start paring it down.”

Hedgcock’s enduring fascination has been fuelled, he says, by a similar motivating force as Bowen’s own work; righting wrongs. “I felt Bowen deserved better than the niggardly note taken of his life and death,” Hedgcock says, adding that the crumb trail becomes more difficult to follow with each passing year. “All too many people who might have been helpful have gone to the great pavilion in the sky.”

Bowen’s own demise was grim but perhaps predictable; that foray into self-administered surgery lent him tabloid infamy, but it also began a chain of events that resulted in a lonely and premature end to his life.

Having described himself as a confirmed bachelor for much of his life, Bowen surprised many by belatedly marrying a widow named Anne Valerie Jodelko in 1974 and becoming an unlikely stepfather to her two visually-impaired sons, but by then he’d lost almost everything; the amputation spooked superiors and curtailed his intelligence career, and if to confirm his lifelong suspicion of Britain’s establishment, he was heartlessly turfed from Whitehall only months before qualifying for a considerable pension.

Gone too were The Cricket Quarterly, plans for a lavish, multi-volume encyclopaedia of cricket, plus one of the game’s most significant book collections, and most of his other worldly possessions. The piles of letters, which were once fired from his typewriter by the dozen and winged their way all over the world, reduced in frequency (“I am nearly drying up,” he wrote to Mullins), replaced by phone calls to the pals who’d still answer. “Bowen he-ah!” he’d bellow into the phone.

Maj Rowland Bowen died at the age of 62 in early September of 1978, in the humble surrounds of Buckfastleigh, Devon, his spiral into poverty, obscurity and ill-health unremarked upon by most of the cricket world. In its concise obituary, in which Arlott must surely have had a hand, Wisden labelled him “one of the most learned cricket historians”.

“We had many battles,” Bowen’s widow once told Hedgcock, “but were always glad in the end to be together.” The Cricketer, for whom Bowen had once written with alacrity and gusto, afforded him only 35 words by way of a send-off. Even Wynne-Thomas – himself labelled a “buffoon” and cast aside by his old colleague before the end – felt the slight keenly: “Bowen was worth more than that.”

In the mid-1990s, Wynne-Thomas published a study of Bowen’s life and work, praising him as “the progenitor of much modern cricket scholarship and thinking”, and positing that Bowen’s texts “tower above the works of his contemporaries”. Yet were it not for obscure journals and Hedgcock’s decades-long pursuit of the trail, we would know little of one of cricket’s greatest, most complicated and fascinating friends.

Rowland Bowen’s final written correspondence with Pat Mullins, dispatched 20 November 1971 and spread over two long full air letters of closely-spaced text, suffices as an apt summary of his life and intellectual wanderings, journeying in and out of Archives de France before traversing arcane dictionaries, racial politics, Bodyline, Tory “torture” in Northern Ireland, Bradman (“by 1934 he was past his heyday”; in 1930 he was “a bore”), and the ongoing embarrassment of Australian monarchism.

Then, out of nowhere, on account of some trivial point of disagreement, Bowen did what he’d always done and abruptly ended yet another relationship with a well-meaning friend: “Well there we are,” he wrote, “and if this is to be the end of our correspondence, in one way I shall be sorry: but in another, not at all.” Brilliant and barmy till the end, Rowland Bowen had cut another one free.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion